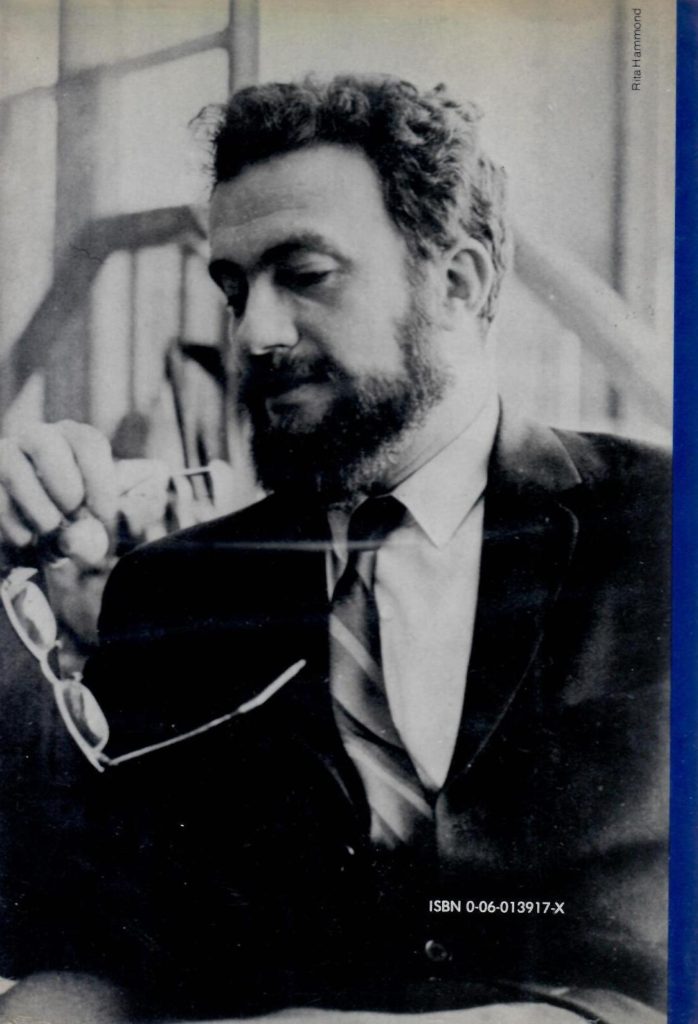

I was introduced to the work of British poet Philip Larkin (1922-1985) in the early 1980s. His voice is arresting and nigh unduplicatable (wry to the point of cynicism, unblinking, speaking of what is broken–personally, familially, culturally–with a certain precise relish in naming) while his technical brilliance anchors his disaffection in pitch-perfect music, deploying a kind of carillon-centered bell-ringing that is at once lofty and gritty.

Larkin was nothing if not self-aware. In In 1979 he told the Observer: “I think writing about unhappiness is probably the source of my popularity, if I have any… Deprivation is for me what daffodils were for Wordsworth.” Paradoxically, perhaps, Larkin renders (in the noisome sense of extracting tallow from carcasses) great beauty from unlikely sources, such as an unswerving concentration of the state of boredom or betrayal inherent in platitude or questioning of faith. At the same time that he appears to be tearing down, he is simultaneously building up. In this way, he offers his own homely-wrought candle with which to light the darkness he finds in the facts of human existence.

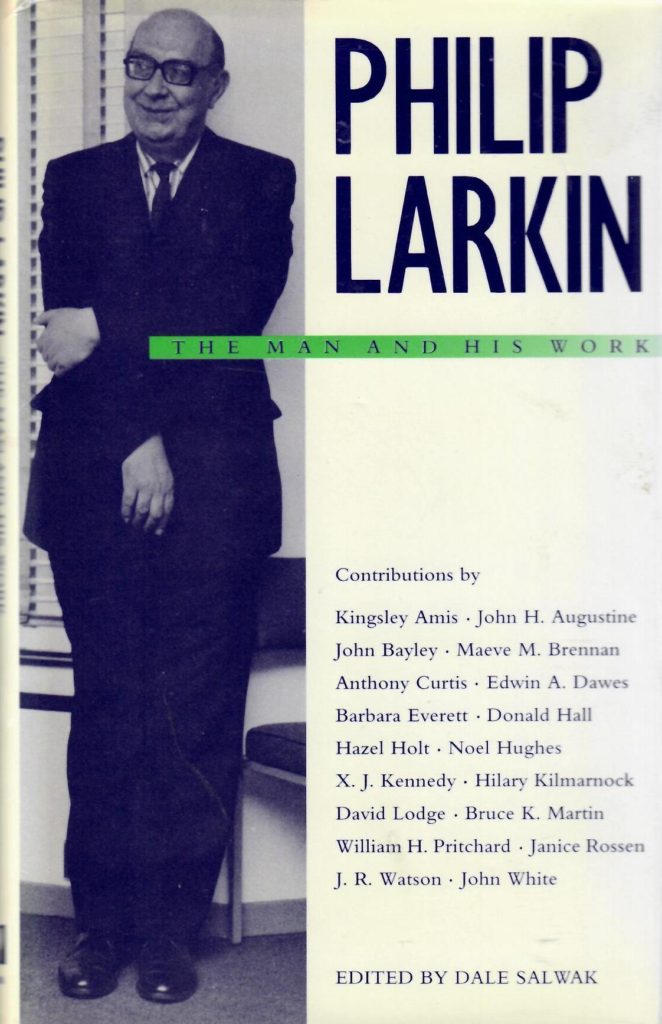

Philip Larkin: The Man and His Work, edited by Dale Salwak (Macmillan Press, 1989) is a collection of perceptive essays by the friends, critics, and artists who knew him and his work well helps to illuminate further his temperament, his intention (among them, to “out-Auden Auden as he gazed at the grim landscape of post-war Britain from his post a Librarian at the University of Hull), and his achievement. A Christmas gift from another poet and friend (Thank you, Sally!), it has been in my library since 1989. In it, I have tucked an article from Vanity Fair (April 1993) by Christopher Hitchens, a journalist given to similar excoriations of widely held pieties as Larkin himself. The article appeared after a posthumous volume of Larkin’s letters was published, and takes Larkin to task for assorted bigotries and class privileges. The article opens, “Even while he was still ambulant and breathing, Philip Larkin was a Dead White European Male.”

There is no question that Larkin was a difficult person–this curmudgeonly, confirmed bachelor, jazz critic, recluse–but he is also an acquired taste, and sometimes nothing else will do. Rather like medicinal bitters, there is something bracing, clarifying, and tonic about reading Larkin, reading about Larkin, noting Larkinesque details in a previously overlooked genre or physical landscape. And, much as he might cringe to hear it, there are moments of quiet beauty and even happiness in his poetry that continue to uplift the reader. There are also evidences of unselfish friendship in his life. (Without him, the novels of Barbara Pym would have been long out of print, for one example.)

Paradoxically, perhaps, Larkin’s poetry was much loved during his lifetime, and his reputation as a poet has never dipped. This person who appeared to scorn affection–and perhaps disliked himself most of all–did love poetry. That is apparent in how much care he lavished on polishing to a high gloss each line, each syllable, however sometimes irascible. The sharp-toothed pain-born jazz music of his verse poured out of his fingers onto the page. In the end, I would argue, his wore his heart on his sleeve.

Regarding the Poem “Dandelion”:

The poem is self-explanatory with perhaps one note. (“Piscan”, a name for the dandelion in North Italy, is the informal Italian for “dog pisses.”) I think it was a felicitous convergence that today’s inspiration of the letter “D” and the humble subject of the dandelion could be paired with the acerbic poetry of Philip Larkin, but you be the judge.

Until tomorrow,

LESLIE