Papyrus, is, of course, where we get the English word near and dear to the hearts of all readers and writers: paper!

Emily Dickinson famously wrote, in her poem known as #1286,

There is no Frigate like a Book To take us Lands away, Nor any Coursers like a Page Of prancing Poetry – This Traverse may the poorest take Without oppress of Toll – How frugal is the Chariot That bears a Human soul.

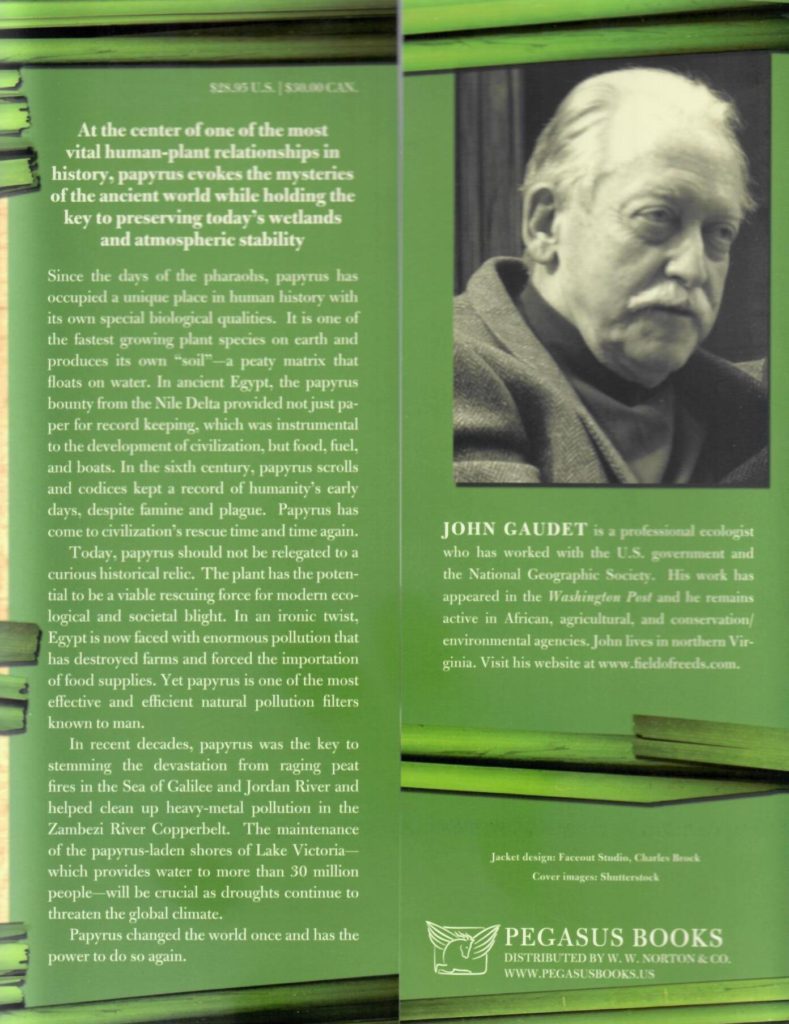

It was in reading this (well researched, pointed, and gracefully written) book on the glorious past and exciting future of the papyrus plant that I learned that in a near-treeless country, it was papyrus that allowed Ancient Egyptians to construct their first vessels to navigate people, animals, and goods up and down hundreds of miles of the Nile River, as well as to create the papyrus scrolls–and and international market for the papyrus medium, precursors to the books we treasure today.

Environmentalist Gaudet suggests that just as the papyrus changed the course of history (and allowed us to record, and, therefore, have a sense of history as a species) this reed plant could be of great service to humanity and other life forms in allowing us a cleaner, more biodiverse, and water-rich future. (His website, www.fieldofreeds.com, has much more information, including video clips.)

Regarding the Poem “Hamartia”:

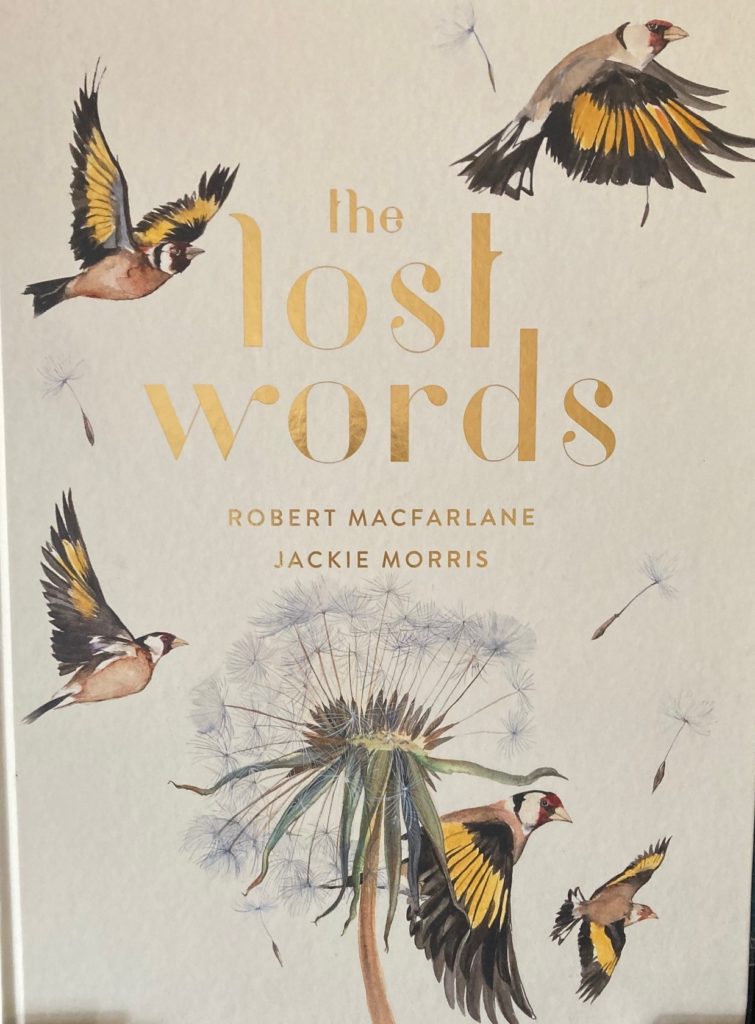

This poem, as you might surmise, is ripped from today’s New York Times headlines–climate accords, ambitious carbon reduction targets, and new information about the primordial feature of the universe, the Black Hole. All this made me think about the literary idea of the tragic flaw, usually applied to a heroic individual, and wonder about it collectively, wonder if it is woven into the fabric of the universe itself, and, if so, what might we do with that? Tomorrow, I think, to balance out, I shall have to condense my gaze into a haiku on a dandelion.

(Thank you to those who elected to receive this year’s April poems via email! Knowing you are there is enormously helpful as I write new work. I appreciate the chance to share without technically publishing, so that I will have the option later to revise and send this new work to literary journals. If you are not receiving the poems but would like to, let me know, and I will add you to the list.)

Garden Update:

Since April 1st, there has been lots of action in the garden, and more will come before my final garden update on April 30, so I thought I would share a few of the highlights now. (For those of you outside of Minnesota, now that we have had weather that veers from 70+ degrees Fahrenheit to below freezing, with sun, wind, rain, and snow (sometimes all in the same day.) These garden denizens are not only beautiful, they are brave and hardy. It will be May 15 (as recommended by Patricia Hampl in her Romantic Education — her father own a greenhouse in St. Paul) before we dare set out the plants we have wintered over and fill in pots with new annuals.

Until tomorrow, “Happy Earth Day, wherever on Earth you are!”

LESLIE