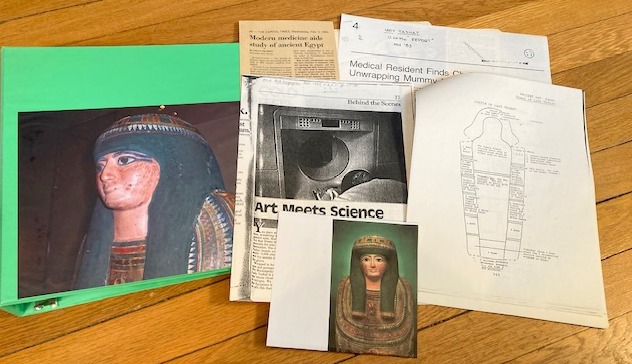

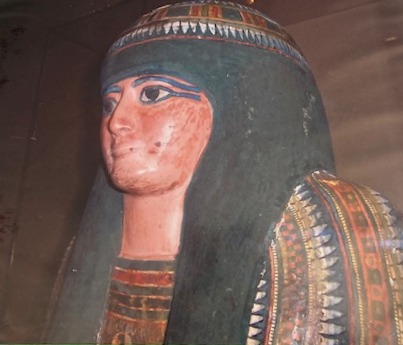

The fifth section of Geranium Lake is filled with a long, nine-part poem that took me more than twenty years to complete. “Lady Tashat’s Mystery” began as a response to exploring the permanent collections of the Minneapolis Museum of Art. It evolved into an inquiry about what we, individually and collectively, chose to preserve and display, what effects that has, what it says about us. Museums–temples to the Muses–are very important to me. During the pandemic, I missed their closure more than the closure of restaurants or other public spaces. I find museums lively and stimulating. At the same time, whenever I am in a museum, I am keenly aware of the presences of those long dead, and, in a way, of how culture depends upon conversations with those long departed, upon questions of why the dead did as they did and made what they made–and what we continue to make of it all.

This particular “exhibit” raised more questions than I can answer, even after I spoke with a curator and did as much reseach as a lay person could do. Though I continue to wonder and ponder, I think now that there is no answer or, rather, the answer is simply the mystery of existence.

Below are the first two sections of the poem, and a glimpse of part of my amassed background information.

Lady Tashat’s Mystery for Leo Luke Marcello That which is hidden might be preserved. One day it will come to light. I. Reading the Bones Under the desert sand, Under the rock. Behind the false door, Behind the true. Beneath two heavy lids And two painted smiles, Beneath the linen tapes Stiff with unguent. I am revealed. I can tell no more. But if my riddle begins to tap Like an ibis bill Inside your head, Then you already have the map, And I, though chill, Am not utterly dead. II. The Museum-Goer The snows of Minneapolis are white as marble dust and cut the nostrils like fragments of bad dreams. The Institute, too, is white: stone, a slippery mountain, behind the delicate tepees pitched on a frozen lawn. Inside, treasures of six continents lie in cold cases, on view. I have been here before to see the quilts of dead women and the brushed smoke and sunlight of dead men. Each time, I circle the Poet's Mountain hewn from a single piece of bluish jade. To one who looks closely, it is possible to see drunken men winding up the side of a glassy mountain, tottering unaware near precipices, over slender bridges, their thin beards quavering with excitement. They are part of a world as fragile and polished as the road they tread. From a distance the mountain looks like a heavy cloud or a dragon's blue egg. Do you suppose the poets know this? Do they think that if they get their words just right the mountain might split open with a clap of thunder? If so, would this be praise?

May this be a day when you, too, enjoy grappliing with an unanswerable question! LESLIE