One of the best things I learned in graduate school was the work of W. D. Snodgrass. His book-length, Pulitzer Prize-winning poem, “Heart’s Needle,” was published the year I was born but I had never heard of it until I was given a Xeroxed copy of it in a seminar class. (I now have a treasured copy in proper book form!) Snodgrass came to McNeese when I was a student there and read from his then new work, what became the collection, The Death of Cock Robin (University of Delaware Press, 1989). He was a magnificent reader of his own lyric poetry (even singing sections of it, at times, wholly effectively) and, in every way, a big presence.

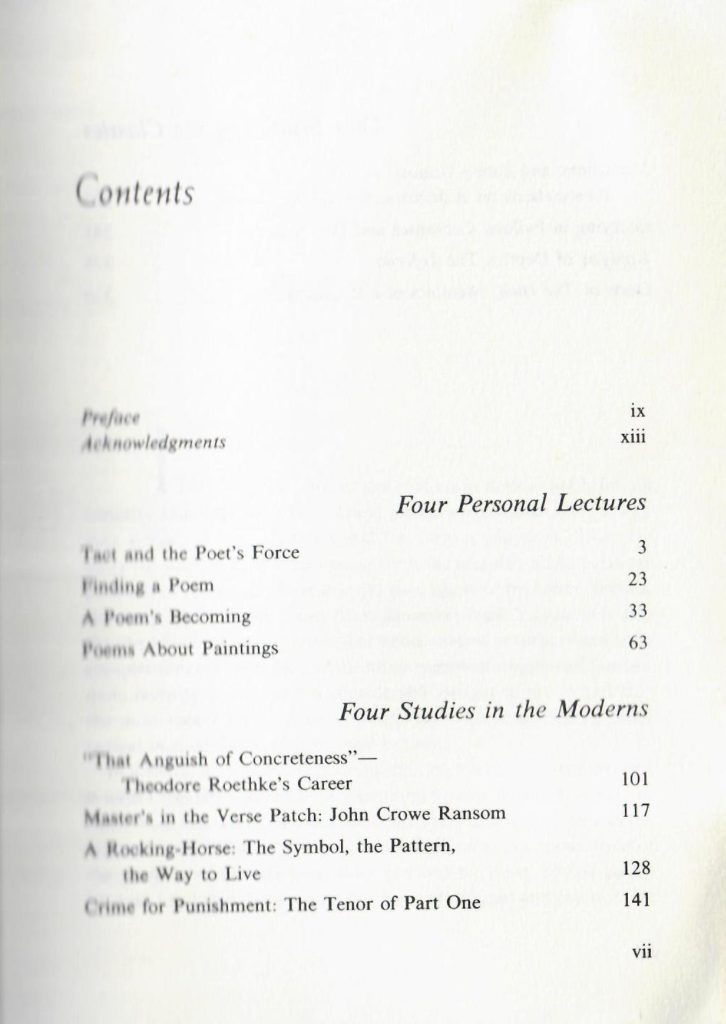

Not long after encountering his poetry, I was also given a Xeroxed, stapled in the corner, copy of his essay, “Tact and the Poet’s Force,” which I still have, which treats, among several topics, the power of what is not said. I find Snodgrass’s prose to be as lyrical and muscular as his poetry, and I am particularly drawn to read his thoughts on works I know pretty well already, as he always sees new-to-me elements and communicates them with eloquent gusto.

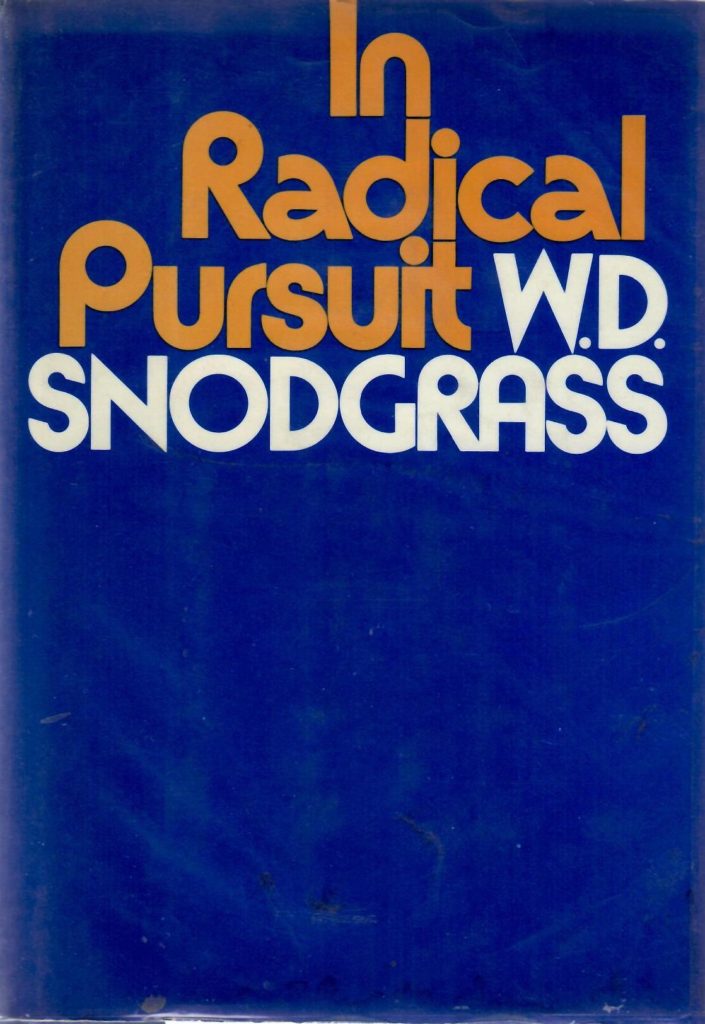

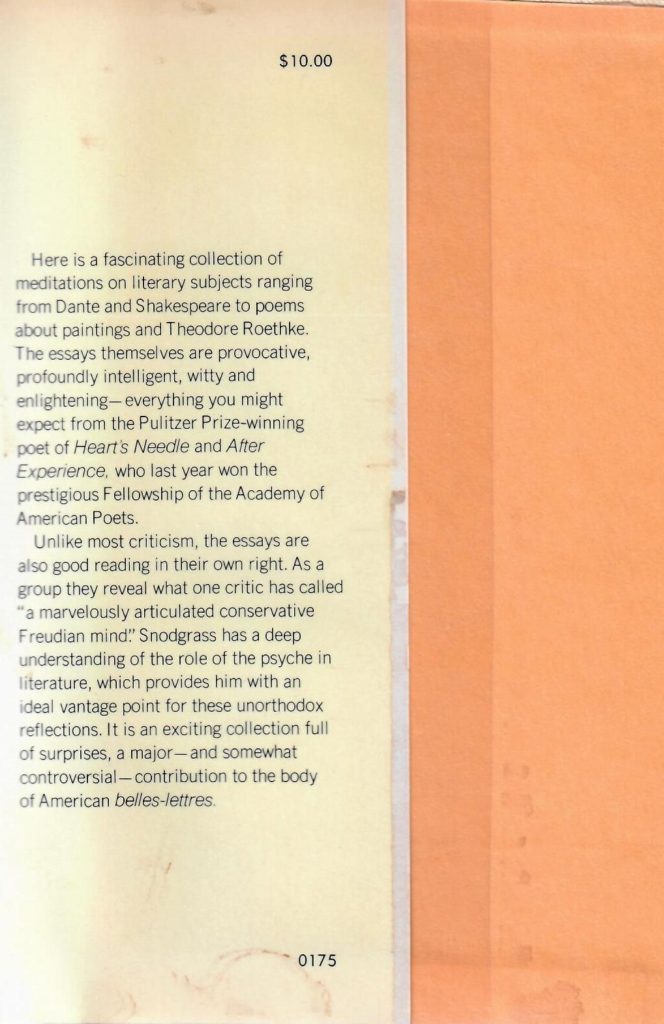

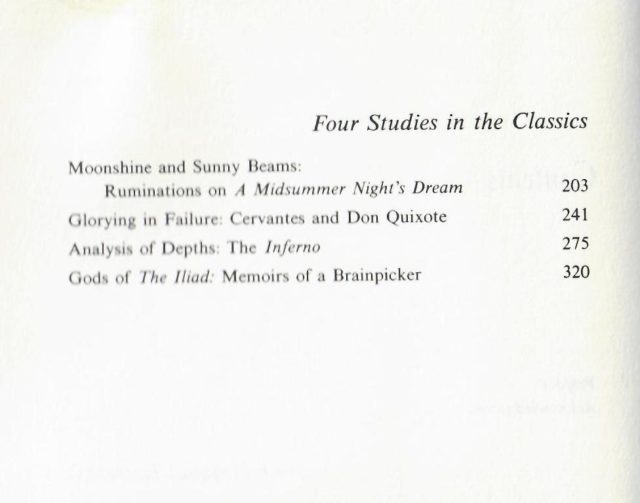

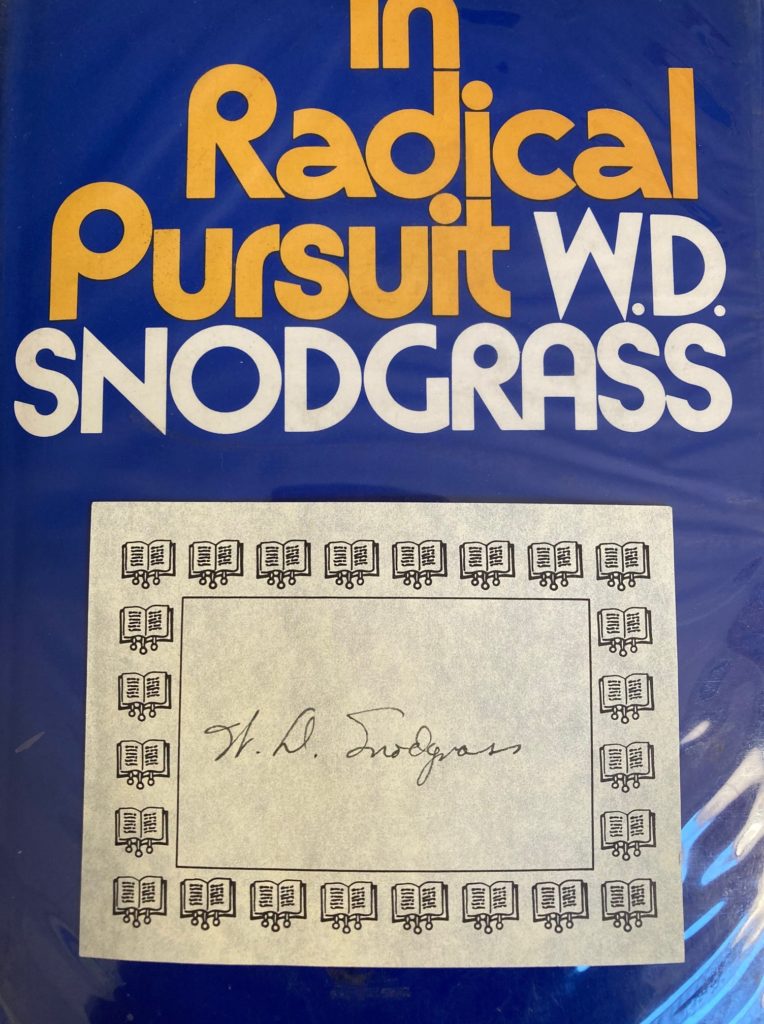

Today, in honor of the global celebration of William Shakespeare’s 457th birthday, I would like to recommend the Snodgrass essay, “Moonshine and Sunny Beams: Ruminations on A Midsummer’s Night’s Dream“, in his collection of essays titled In Radical Pursuit (Harper & Row, 1975). In this essay, Snodgrass begins with all the questions surrounding the title and action of the play–Who is the dreamer? The poet-playwright? Any or all of the characters? The audience?–and who gets dreamed? What is the nature of the phenomenon of dream/nightmare? Throughout the essay, Snodgrass turns over the phrases and assumptions of the drama and keeps coming back to the need to understand, so well as can be done in the strong light of day, the nature of the Moon, symbol of enchantment and illusion, particularly the illusions patriarchal society invests in the power of fathers over children (which, as we remember, launches the action Shakespeare’s comedy). I read this and delight in the insights into the Elizabethan poet and playwright, and I think of Snodgrass’s first masterwork, Heart’s Needle, so autobiographical that it has been cited as a major work of mid-century confessionalism (a term Snodgrass disliked), which is in part a long lament about the powerlessness of the divorced father who sees his daughter growing up and growing away from him.

Regarding “To a Grackle”: Today’s poem features a bird common here, but one which William Shakespeare would not have known. Still the grackle puts me in mind of him, not only of the Chandos oil portrait of him, where he looks a little crow-like to me, but of his testy and protesting “Dark Lady” sonnets, in which the speaker is (often unwillingly) entranced by unconventional beauty. I like to think that had Shakespeare seen a grackle, he would have made at least one sonnet for it.

Until tomorrow,

LESLIE