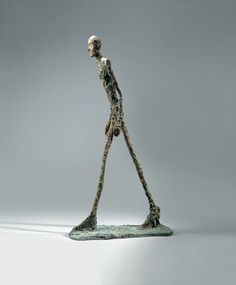

Giacometti

for my father

“…the traces of an uneasy compulsive activity shape

the image of a separate presence.”

“He sculpted not the human figure but “'the shadow that is cast.’”

Mornings, wearing a tie, you took the train

to Flinders Street Station, in the city’s heart.

Evenings, sometimes you dallied in the park,

watched the black ornamental swans, sheltered

from the choppy Yarra on their placid lake,

crown jewels of the Royal Botanic gardens.

Other days, you’d cross Prince’s Bridge but veer

toward the brick archway of the art museum,

the one fronted by a glass wall running with water.

One time, you showed us all how you could place

your hand on that window sculpted over by flow,

force the cascade, like a rock in a stream, to part;

next, you increased your slight magic by lifting

your hand to restore an unceasing waterfall,

as though you had never been there at all.

One evening, you wandered in. I imagine

you restless in that space, pecked by artists’ visions,

driven toward their shop by the known rubric

of commerce. Why, otherwise, would you carry

home a long, thin volume for me, praising

the sculpture of Giacometti? Yes, I could see

“L’Homme qui marche,” thin as a railroad spike,

bent, pitted with weather, long nose sharp as a blade,

but I didn’t see, until now, how he resembled you,

your views, your profile, your obdurate strivings.

Remember, children don’t always track these things.

Leslie Schultz

My father was a math-physics double-major. He worked first as an engineer and later in computer science. Although identifying with scientists, he showed steady but idiosyncratic bursts of appreciation for arts and crafts. He liked many things, including: carved wooden duck decoys, coins, stamps, science fiction, spaghetti westerns, the song stylings of Johnny Cash, poetry that had been popular in his grandparents’ youth, and the irreverent lyrics and melodies of mathematician Tom Lehrer.

Today, I remembered the one time he brought me home a heavy-to-hold art book. It was a hardcover catalog of the sculptures of recently deceased Italian surrealist sculptor Alberto Giacometti. Then, as now, I was puzzled by this gift, but also touched by it. This morning, I am recalling a line from Dad’s favorite poem by Robert Service, “The Cremation of Sam McGee,”

On a Christmas Day we were mushing our way over the Dawson trail.

Talk of your cold! through the parka's fold it stabbed like a driven nail.

If our eyes we'd close, then the lashes froze till sometimes we couldn't see;

It wasn't much fun, but the only one to whimper was Sam McGee.

This was a poem he could recite from memory with great gusto, always coming down hard on that key syllable, “stabbed.”

To refresh my memory of this sculptor and his work, I looked him up. The first quote at the start of my poem is from a BBC documentary, “Giacometti,” from 1967, the year after the sculptor’s death, the second is from his own analysis of his work. This figure was just my Dad’s height, six feet. I think Dad would be interested to know that it holds stratospheric value today, not only among art critics but among deep-pocketed art patrons.

I am still not sure I understand it, but today it looms large, commanding my attention.

LESLIE