As all journeys do, this one began at home. On Tuesday evening, January 22, I read via Zoom with the Crazy Wisdom Poetry Circle. I went to sleep with the voices of other poets in my head, with a feeling of precious community. That experiences was a good precusor for the next few days.

Day One: January 23, 2025

The next morning, my friend and neighbor, poet Susan Jaret McKinstry, headed north and east toward Appleton, WI, where our first reading was scheduled at The Book Store on College Avenue that evening. For a three-and-a-half-day journey, a lot of impressions accrued. The (mostly visual) highlights below share some of these. Still, it might prove an epic journey for a reader–be forewarned!

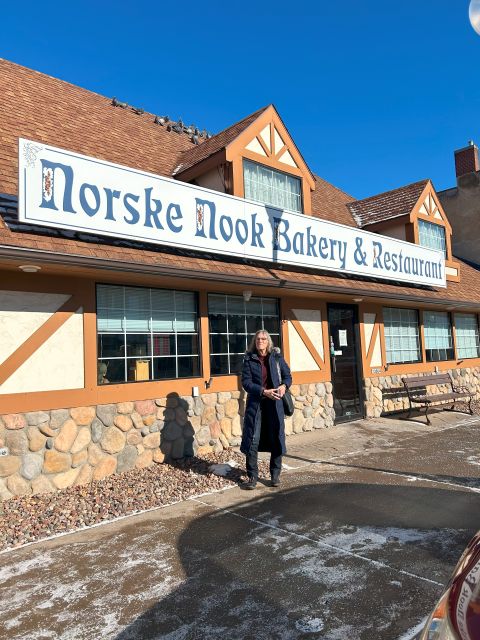

Part of the journey for me was a trip down Memory Lane. We stopped first for breakfast in Osseo, WI, a tiny dot on the map off Highway 10 with a restaurant my parents and sister and I had visited before, the Norske Nook–famous for its pies.

After breakfast, with Susan’s indulgence, we visited the nearby Quilting Nook and the City Park, where I tossed one of my Dad’s coins. The nickel made a satisfying rattling sound as it disappeared into large-mouth bass sculpture and then clincked through, as though being rejected by a vending machine. On the third toss, it slipped into a dark crevice to await spring.

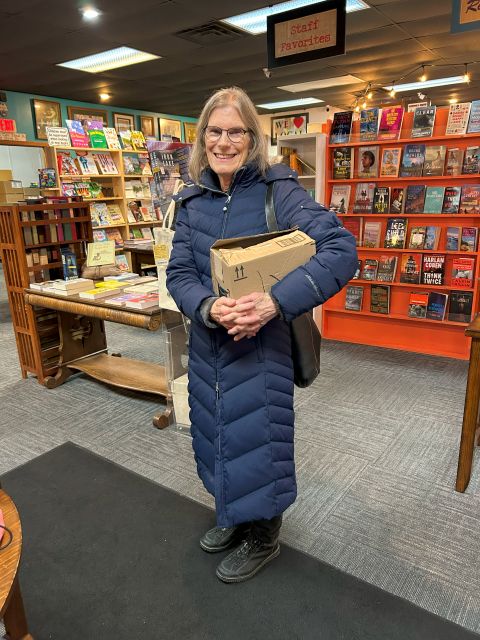

We arrived at our hotel, the Paper Valley Hilton on College Avenue, just at dusk. The reception desk had a whimiscal book wall, and our quiet and spacious room had a delightful view of a skating rink. We were soon on our way to The Book Store for our first reading–it turned out to be a delightful venue, and the small group of listeners (just two, former students of Susan’s!) made for an interesting conversation afterwards between the four of us. I was pleased to read a number of poems inspired by the Fox Valley. Afterwards, we dined at the Vince Lombardi Steakhouse at the hotel. It offered vegetarian options and momentos from the collection of the legendary coach himself.

Day Two: Friday, January 24, 2025

Up early, we indulged in Starbucks lattes (thank you, Susan) and then drove to three places once part of my family landscape.

First, we motored over to nearby Menasha and found 537 East Broad Street, the house my father’s paternal great-grandparents, Emil and Katherine Schultz, built and where my grandfather, Charles Schultz, grew up. A coin was duly tossed into the Fox River.

Next we returned to Appleton and stopped briefly at the house where I briefly lived, before heading off to college, at 3311 North Rankin Street.

Our final morning stop was at West Lorain Court in Appleton, a house built by my great-grandmother, Mae Peterson Danielson, and lived in with her second husband, James Danielson, and after Grandpa Jim’s death, while I was in high school, inherited by and inhabited by my father’s parents, Phyllis Peterson Schultz and Charles Schultz.

The house is arranged on its triangular lot so as to have the maximum of sidewalk. It was my good luck that we’d had a dusting of snow the night before, and that when we saw the current owner, Bob, shoveling his walk, Susan encouraged me to speak to him. I am glad I did! It turns out not only did he know my great-grandfather but he had been his paperboy decades ago.

We began talking, and he shared many memories before inviting me in to meet his wife, JoAnn. It was lovely to see the diningroom where I recall meals of pot roast and lemon meringue piebeing served, and the kitchen where I recall doing dishes. I forgot to ask about the rhubarb patch behind the house that my great-grandmother loved, but I did get to peek into the garage and see the vintage car Bob is restoring. I left them with copies of two of my books and a promise to send them the poem I had read the previous evening, “Sylvan”, dedicated to my great-grandfather, who came to this country from Denmark in order to work as a lumberjack. Later he ended his career as the accountant for Knoke Lumberyard in Appleton.

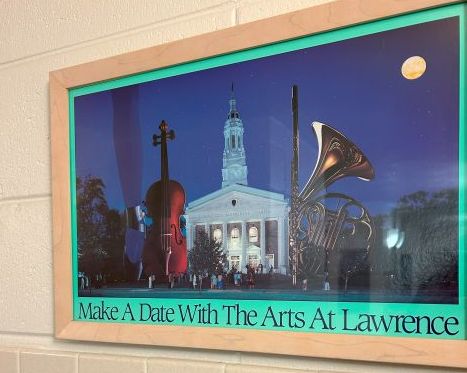

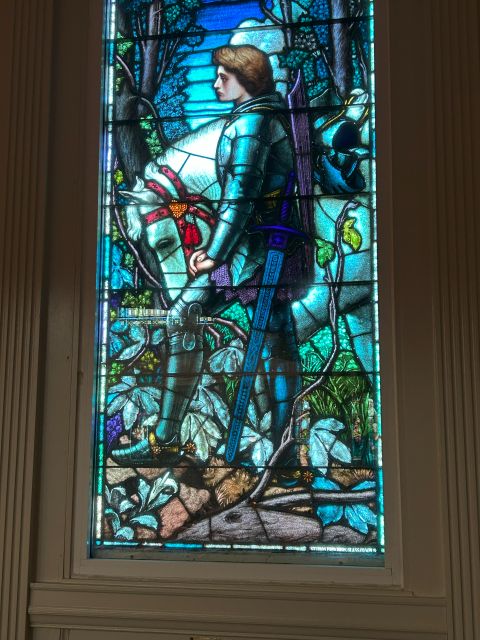

After that delightful chance encounter, Susan and I went to the Lawrence University Chapel to hear poet Patricia Smith give a convo talk.

We arrived early enough to soak in the beauty of the chapel’s stained glass versions of Pre-Raphaelite paintings. The chapel was filled to capacity. Lawrence professor Melissa Range introduced Smith as one of her long-time heros. Having read some of her recent work, it was a pleasure to hear how Smith, a noted spoken word artist, brought her poems to life.

After the Convo, Susan and I were able spend quality time with some old and new friends. We were able to have a leisurely conversation with poet Melissa Range at nearby Lawless Coffee Shop. Ranger is a member of the English Department Faculty at Lawerence, sharing a position with her partner, poet Austin Segrest. I had connected with her at a Zoom workshop on the modern sonnet a while back (best workshop ever!) and was elated when she agreed to contribute a blurb for Geranium Lake. It was wonderful to get to meet her in person, and to ask her to inscribe my well-read copy of her collection of poems, Scriptorium.

That evening, we attended one of those rare and perfect dinner parties at the home of family friend, Brigid Vance. Tim, Julia, and I met Brigid when she was a Carleton psychology major in her senior year. She lived next door and did babysitting for Julia until she graduated. Several degrees later, she is a professor of history and co-chair of the Asian Studies Department at Lawrence with a forthcoming book on research focuses on the intellectual and cultural history of dreams and dream divination in late Ming China. She invited us to be part of a special dinner she and her wife, Maria Luisa, were making for Maria Luisa’s brother, Elias in honor of his 40th birthday. Ranger and Austin came, too. Maria Luisa and Elias grew up in Venezuela, and we were able to experience special food and drink from their home country, as well as lively conversation. We also got to meet three adorable dogs–Eenas and Hector (miniature schnauzers) and Venus (a dachshund)–all of whom were sporting sweaters due to the compelling cold.

It was a warm and lovely way to spend a frigid evening away from home.

Day Three: January 25, 2025

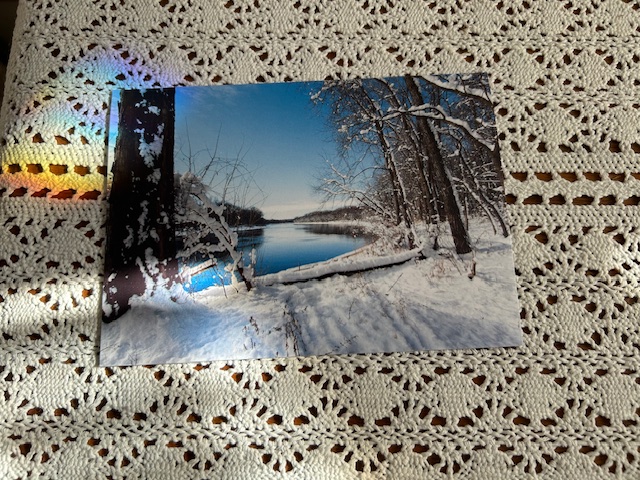

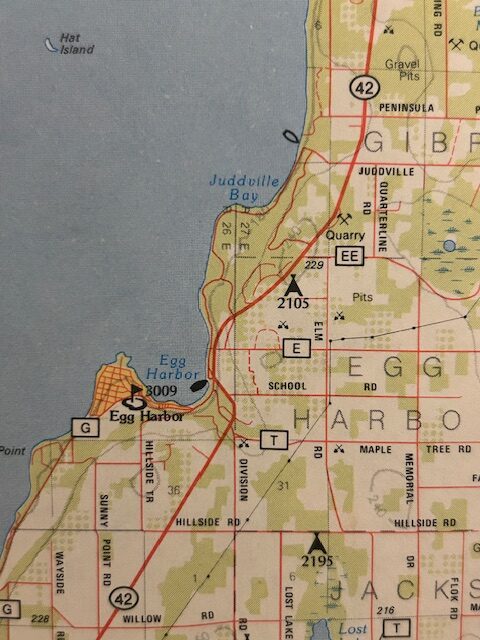

On Saturday morning, we drove north and east to Door County, a place filled with good fishing, cherry orchards, artist’s studios, and incredible natural beauty in all seasons. We stopped briefly in Egg Harbor, where I had never been before, though I had vividly imagined it during my Lake Charles years. That is when I wrote the poem, “Egg Harbor, Wisconsin” — included in Still Life with Poppies: Elegies. It seemed an appropriate place to leave a coin.

Egg Harbor is just a few miles from our main destination, Write On, Door County, an incredible literary center outside of Juddville.

This literary center, a thoughtfully designed space filled with natural light and sited on 50+ acres of trails, across the road from their writer’s residency house, is a place as well suited to quiet contemplation as it is to events and programs. Katie Dahl, a local singer-songwriter (and Carleton English major alum!) with deep roots in Door County, was one of their first residency recipients. She invited Susan to participate in an event with her, and I was delighted to be included in the program. Having listened to her CDs over and over, I enjoyed the chance to hear her play and sing up close, especially in a place with superb accoustics.

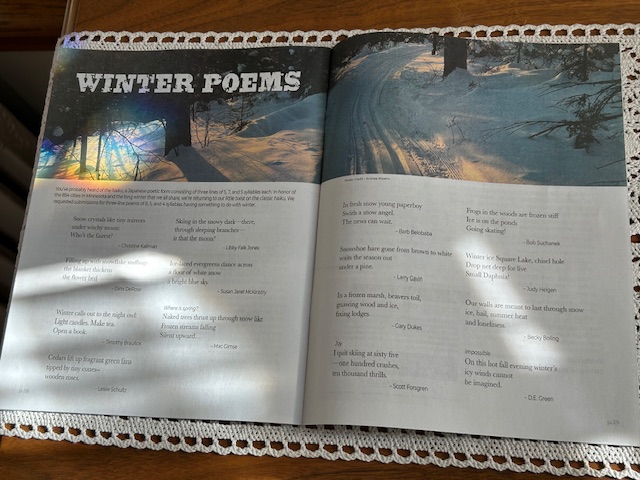

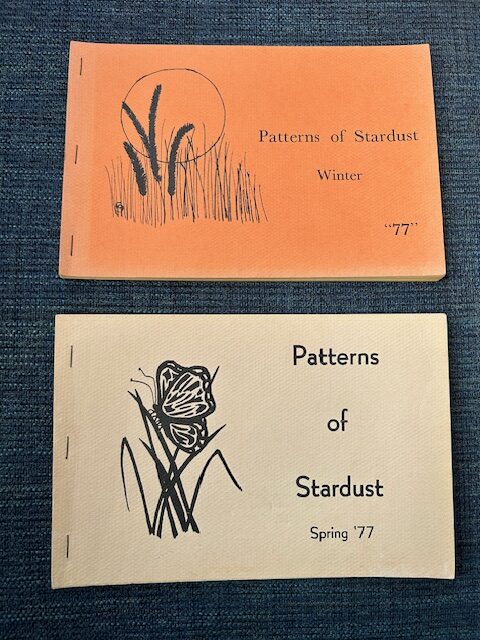

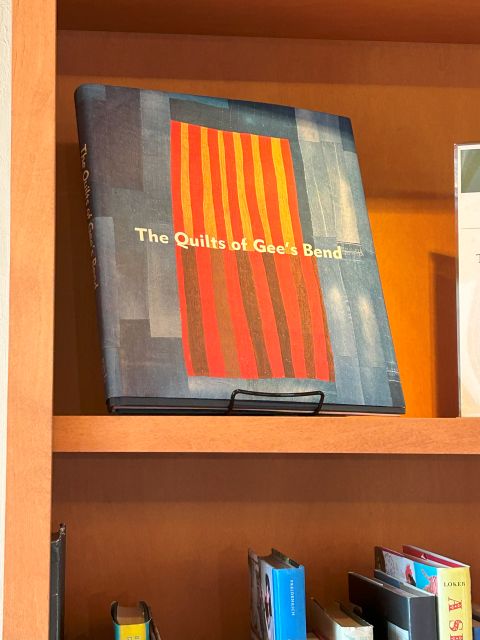

Katie pulled in a large and welcoming crowd. Poet Al DeGenova, who serves as Executive Director of Write On, Door County, introduced us. Then Katie played first, then Susan and I read poems, and then Katie took more requests and told stories of how her songs came to be written. When I saw this book, also in my own library, right behind the podium, I knew that I had to read my poem “The Book of Quilts” as well as my poem about Egg Harbor (both from Still Life with Poppies: Elegies) and a few from Geranium Lake. Susan read both some new work and selections from her incredible collection, Tumblehome.

After the event, we followed Katie to the home she shares with her husband and bandmate, Rich, and their son, Guthrie.

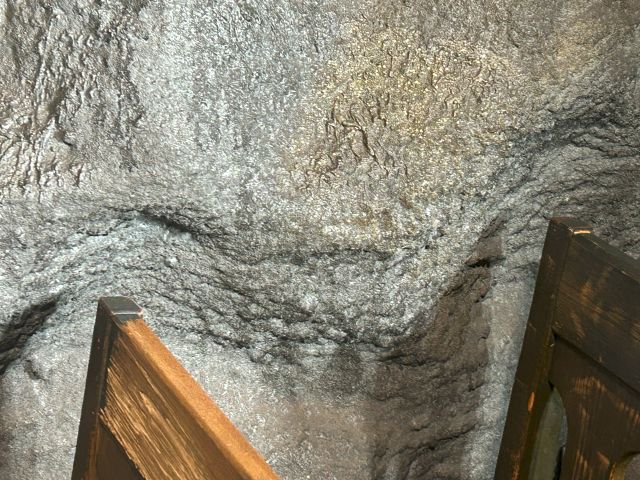

They had kindly invited us to stay in their guest house–a very comfortable strawbale construction with tile floors with radiant heat–the ultimate in minimalist luxury. They also invited us to dinner, and it was fragrant and delicious–vegetables and red beans, homemade naan, and a pumpkin-spice cake adorned by Guthrie with glorious cream cheese frosting.

After dinner, we relaxed with Katie, Rich, and Guthrie–the perfect end to an unforgettable day. Thanks to Guthrie, we even played charades!

Day Four: January 26, 2025

Sunday morning found us on the road for home. This time we stopped briefly in Bailey’s Harbor for two kinds of fuel (gasoline and caffeine), and enjoyed a local coffee shop called “Pinkey Promise.”

For lunch, we stopped in Wausau, home of ginseng farming, memories of old college boyfriends, and quirky eateries, including the Wausau Mining Company. As Susan said, “They really commit to a vision!” Veins of gold glinted here and there, canaries (sadly, stuffed) hung from the shaft interior (dining room) and even in the ladies room. The ambience was more memorable than the food for me, but it was fun to sample local culinary color and avoid fast food chains.

Before dark, we drove into Northfield, glad to know that we had returned with many good memories, and glad, too, to know we would sleep in our own beds!

If you made it all the way to the end of this saga, thank you for your stamina!

LESLIE