The Crazy Wisdom Poetry Circle, based in Ann Arbor, Michigan, but offered now through Zoom, offers workshops every second Wednesday and readings by poets every fourth Wednesday. Hosted by Michigan poets David Jibson, Lissa Perrin, and Ed Morin, each reading is followed by an Open Mic opportunity, and all events are free and open to the public.

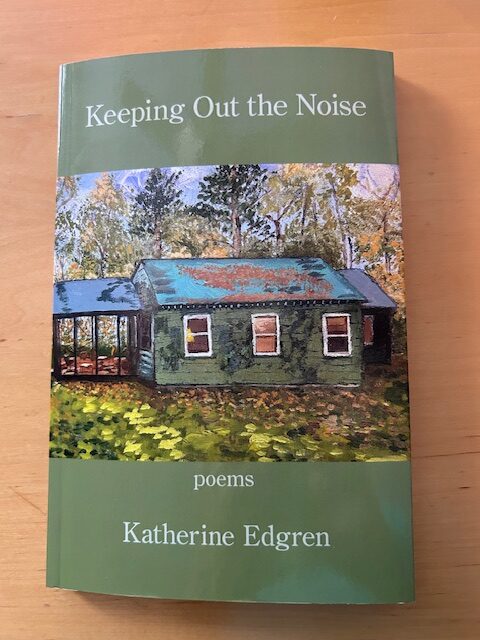

On Wednesday, January 22, 2025, I participated in a Crazy Wisdom reading, followed by one with my friend, Michigan poet Katherine Edgren. These two readings are now available on the Crazy Wisdom YouTube Channel (along with a host of others.) If you missed the live event, you can see it NOW. (See below for a list of poems read.)

The next reading, scheduled for February 26, 2025, is with a phenomenal poet, Ron Koertge who has had poems twice in Best American Poetry and grants from the NEA and California Arts Council. His novels for young adults won two P.E.N. awards. An animated film made from his flash fiction, Negative Space, was shortlisted for the 2018 Academy awards. Billy Collins calls his presentations “deliciously smart and entertaining.”

For more information, please visit the Crazy Wisdom blog.

Poems I Read on January 22, 2025

"The Craft of Poetry"

"Ice"

"The Book of Quilts"

"Geranium Lake"

"A Necklace of Fat Pearls"

"Music So Loud We Can't Hear"

"Notes on Design"

"A Gesture of Peace"

"Ichthyography"

"Lady Tashat's Mystery: Sections I & II"

"Self as Portraits"