I have been meaning to post this review on my own website ever since that most excellent and now lamented online journal, Swamp Lily Review, folded. Today, I learned through Facebook that it is Ava Leavell Hamon’s birthday, and that decided me: today was the day to share this review again. Here is it, without modification except for slight formatting changes.

Happy Birthday, Ava!

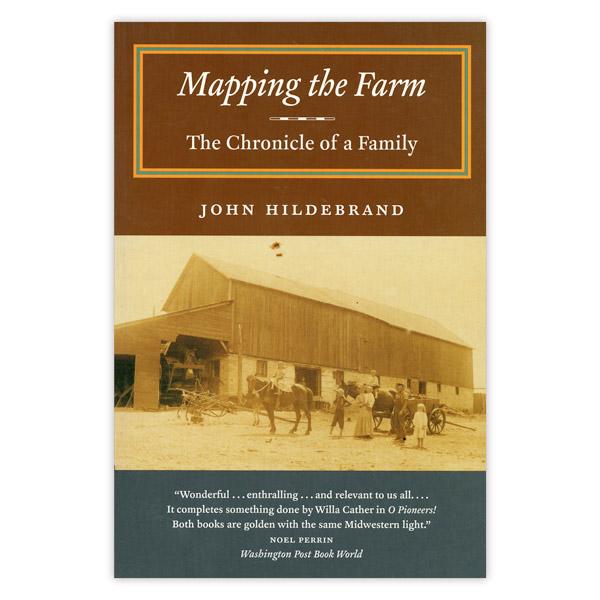

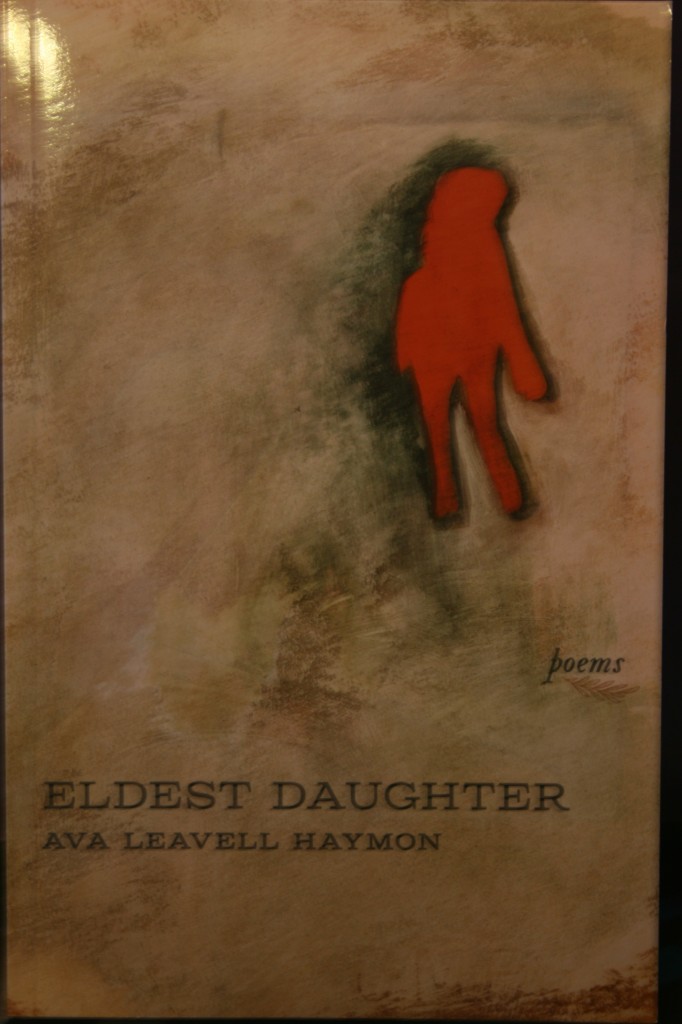

Wielding Words: The Poet and the Preacher A Review of Eldest Daughter: Poems by Ava Leavell Haymon (Louisiana State University Press, 2013; 82 pages) by Leslie Schultz for Swamp Lily Review, 2014.

Preachers are wielders of words and so, of course, are poets. Eldest Daughter, by Louisiana poet laureate Ava Leavell Haymon, is an emotionally wrenching work of verbal beauty that examines how many relationships pivot on the fulcrum of language, echo, and silence. With a narrative compulsion akin to true crime accounts or memoir, this tightly constructed arrangement of poems explores how a dark secret will continue to detonate in the psyche until hauled to the surface; how the truth ‘will out”; and how broken silence is the precondition for achieving the redemption of personal and cultural healing.

This is a collection in which the individual poems gain power from their proximity with each other. The dedication encapsulates, with haiku-like precision, the collection’s subject and themes. Like a haiku, it is presented in a trinity of lines:

for my father

who taught me

the two sides of the human heart

and each epigraph, poem, and section in the collection circles back to this bit of poetic DNA, amplifying and refracting this core relationship of daughter and father, concealing and revealing what the poet learned from the preacher, and showcasing how she chooses to deploy that knowledge.

The first epigraph, a masterful and well known poem by the Sufi mystic Jelauddin Rumi, (translation by Coleman Barks) prefaces the table of contents and gives further information of the poet’s aim toward the father:

Somewhere, out beyond ideas

of wrong-doing and right-doing,

there is a field.

I'll meet you there.

And the rest of the volume is an attempt to do just that: to grapple with issues of righteousness and wrongdoing; to speak where silence was constrained; and to reach a place of reconciliation and recognition rather than recrimination or retribution. Rumi understands the purposeful circularity required for psychological and spiritual forward motion, and his example serves as a touchstone for the poet-daughter’s task. Although Haymon is uncompromising about truth-telling, she also acknowledges, directly and tacitly, the power and strength she has absorbed as the daughter of a powerfully problematic father. The pain throughout is grounded not only by poetic technique and mordant humor but also by a clear understanding of her own authority and, in the end, by a wary tenderness.

Themes

Part of what gives Eldest Daughter its emotional impact and cohesion is the way in which the individual poems and its four sections (“Preacher’s Daughter”, “Why the Ground Hog Fears Her Shadow”, “THE CASTLE OF EITHER/OR: a fairy tale”, and “Daughter’s Fealty”) have been shaped by common themes. Among them, I consider these four to be the most prominent.

1) Recognition of a deep divide between poet-daughter and preacher-father. As the poems make clear, this divide has many root causes: gender, generational differences, temperament, cultural norms, family dynamics, and religious assumptions. But the deepest sundering occurs because of the preacher-father’s lack of appropriate sexual boundaries. His unacknowledged ongoing rape of the daughter; his assumption of entitlement in which the mother, other family members, and perhaps the church communities through which the family travels are complicit; and the three-monkey policy (see no evil, hear no evil, speak of no evil) creates a cataclysmic rupture in this fundamental parent-child relationship. The betrayal is double, since the preacher-father is not only parent but religious authority.

2) Refusal of the poet–daughter to accept the internal and external laws of the preacher-father

The very fact of these poems, the decision to publish them, to dedicate the collection to the father, and to use the father’s full given name within a key poem, shatters the silence and establishes the poet-daughter’s voice as one of authority.

3) Voice: that of the poet-daughter grows more powerful than the booming voice, heard from childhood, of the preacher-father.

The key question from W.B. Yeats’ sonnet, “Leda and the Swan”, (a poem that forcefully pinpoints the inception of the Trojan war to the moment when the father of the gods rapes a girl) is: “Being so caught up/So mastered by the brute blood of the air/Did she put on his knowledge with his power/Before the indifferent beak could let her drop?” Regarding Leda, the question hovers; regarding Haymon, however, the answer is a resounding affirmative. She has not merely ‘put on’ the powers of the preacher, but has assimilated, transformed, and rechanneled them into poetry.

The preacher-father’s knowledge—of mythology, logic and rhetoric, and all the tactics of rough intimidation–is the largest measure of his power. This volume opens with the father-preacher’s voice (multiplied, in a form of mental surround-sound rolling back through many generations, perhaps to the dawn of patriarchy itself) at the height of its power, “the King James roll of those baritone voices/seminary trained, huge without microphones,” on the heart and mind of an impressionable girl, the future poet. Even here, though, it is undercut by the daughter-poet’s perspective, gained over years, as well as her humor and honed poetic skill. The collection is ordered to document the waxing of the poet-daughter’s voice, the waning of the preacher-father’s voice. Perhaps the better metaphor is eclipse: the distant body in the sky is blotted out, at least at predictable intervals, by the shadow of the earth.

4) Insistence on naming, truth-telling, integration and, ultimately, healing.

Eldest Daughter takes us on an elemental journey with special emphasis on the fire of passion, the virtuosity of air, and the sustaining and restoring quality of earth. The journey leads down into the country of rage and shadow. Throughout the collection, the poet-daughter turns to earthiness as the corrective for an over-abundance of inflated high-minded principles trumpeted from the pulpit but undercut by the preacher-father’s actions. The poet-daughter deploys with equal facility the cadences of oratory from the King James Bible and the argot of popular culture. Her jambalaya of high- and low-brow diction makes for delicious dexterous fun, an amalgam of myth-toppling and myth remaking, fiction building and air-clearing. The poet-daughter also insists on reclaiming the deep questioning, relevance, wonder, and connectedness of religion, wresting it from the mangled version of truth represented by of the preacher-father’s vision. She questions: Are these the ties that bind or garroting restrictions that strangle the truth, the personal voice? Part of the strategy of recovery involves naming as a way of reclaiming the world.

In the second poem, “Louie’s: Home of the Veggie Omelet”, the locus shifts from the coercive pomposity encountered in church to numinous revelation in a greasy spoon. In the ekphrastic third poem, “Eva/Ave at the National Gallery”, the poet-daughter considers wryly images of women in religious art and slyly alludes to the palindromic inversions inherent not only in the archetypes presented in the exhibition but also in her own palindromic first name. And in a culminating poem in the volume’s last section (“Roundball”, looked at in greater detail below), the poet-daughter both names and ironically characterizes her father, drawing, apparently, on stories from family elders:

“My father distinguished himself at Louisville seminary

playing center on the basketball team.

‘Big Bob Leavell,’ hero of his Greek class,

‘Mighty rough for a preacher’s boy.’”

The poem goes on to discuss what he has taught his daughters (on the surface about basketball, actually about how to “go man-to-man”, use unnecessary roughness and call it ‘character’). The preacher-father is remembered as angry about the way the game has grown and changed over the decades since he first learned to play it, endorsing (with a highly ironical injection of found humor, since the poet-daughter also leans toward archetypes of pagan Celts). “’The old Celtics,’ he’d fume. ‘Now that was basketball.’” This poem, which comes full circle to an acceptance of the preacher-father’s death (on Candlemas/St. Brigid’s Day/Ground Hog’s Day, a day of totemic importance for the poet-daughter and also the day of an important tournament game that they each attended in their separate ways.) This poem serves as a coda, integrating the themes developed throughout the collection.

Themes as Expressed in Structure of Individual Poems and in the Book as a Whole

The Eldest Daughter poems use a strategy of working on many layers at once. All are built up carefully on the levels of diction, tone, image, dramatic situation, and structure in order to support the key themes of the collection, and then equal care is taken in arranging each poem for maximum effect, again in service of the thematic imperatives. The impression created is one of accretion of sheen and value, of polishing, of burnishing, of—if you will—“pearlizing”.

The speaker of the poems, in her often agonized role as the unwillingly cast scarlet woman-child, reminds me of Nathanial Hawthorne’s Hester Prynne, heroine of The Scarlet Letter. The mood of this parallel is captured stunningly by the book’s cover image of the scarlet floating child-figure drawn from Van Wade-Day’s painting, “Alone”. And it is notable that Hester Prynne named her beautiful daughter—her innocent, natural, but scorned offspring—“Pearl”.

Another frequent technique is of repetition. The images, diction, and various tones recur, adding fresh, refracting interest to support the thematic concerns. When someone important does not, cannot, or will not listen to your voice, you must decide whether to subside into silence or repeat, in varying ways, the central truth, so the reader continues to hear it, and the truth is not washed away. The thematic need for insistent repetition—and with accreting insight—is supported formally in six sestinas; the sestina’s structure, a spiraling and discursive repetition of six end words (rather than end rhyme) cascading through the poem’s 39 lines that requires a virtuoso hand, is an apt container for Haymon’s volatile material.‘

The thematic insistence on uniting opposites in the Eldest Daughter poems is reinforced by the structure of the collection, combining the dynamism and containment found in the symbol of the Celtic cross, four equal arms embraced by, and extending beyond, a circle. In this unified collection the whole is larger than the sum of its parts, fine as those parts are. The unity of the volume derives from four sources: 1) its structure, apparently based on the tools of formal logic and rhetoric; 2) the strong command of and variation in diction; 3) the poet’s muscular ability to render music and resolution from dark material of the most painful order; and, 4) the emotional pressure of the narrative of division and healing, the revelation of one truth lurking behind the guises of the many voices and poetic devices. This central, hard-won speaking of truth is the fruit of tenacious grappling and, for many reasons, reminds me of the Old Testament story of Jacob wrestling during the dark of night until day dawns.

When one wrestles with an angel, there is no chance of besting the angel. The victory comes more like that of the bronco rider: in enduring, in holding on, in not giving out or giving in, and with points added for doing it all with style. Jacob emerges from his wrestling match with a lifelong injury as well as being imbued with new power and purpose. Haymon wrestles with the inheritance of her father’s influence on her life in just this way: injured but victorious, conveying the struggle with power, poignancy, and poetic style. She rides the material of Eldest Daughter with memorable style.

Consider her use of humor throughout these poems. In the first section, there is a comic interlude in “Four-Year-Old Invents a New Curse Word”. In this poem, the poet-daughter makes it clear that she is digesting the concepts of her childhood and thereby reforming them as they pass through her. (The new curse word is “Godshit.”) Recounting the impromptu parlor game at a party, sparked by a young child’s neologism, friends muse over the many different images of God and imagine what kinds of excrement each deity might produce. The poet-daughter thus considers the most earthy of substances and is able to see, recognize, and name it, to refuse to take it, and to laugh at it. The healing power of humor is a necessary tool for downsizing the demons in the head.

“Steam Calliope”, in the last section, illustrates the brutal music, outworn power politics, and mordant wit of Haymon’s vision with a made-to-order objective correlative that she is alert to and deftly deploys. On Independence Day, the poet-daughter is a tourist in a small mountain town, intent on seeing the attractions. When the antique steam calliope arrives, an ear-splitting clap-trap vehicle for well-chewed musical platitudes like “I’m Pop-Eye the Sailor Man”, it plunges her into insights that are as broad as the Industrial Revolution and Christianity and as particular as a childhood memory of her father contending, doggedly, to force the limited octave available with his Baptist church steeple bells to carry hymns, an effort that was doomed to failure:

“…Through trial

and much error, he figured out

a coincidence in range with the old

bagpipe hymns: Amazing Grace,

How Firm a Foundation.

The first line of Joy to the World

stumped down the eight consecutive notes

like an archangel with big news,

and he was OK till heaven and nature

tried to sing toward the end of the stanza.”

Although he can’t foresee it, it will be the poet-daughter of this preacher-father who uses what is at hand to create polyphonic music. Rather than rejecting formative influences, Haymon transforms them into building materials, creating poems in which heaven and nature do, indeed, sing together at last.

The Chiasmus or Crux (Thesis and Antithesis)

In arranging the poems of Eldest Daughter, Haymon uses an extended chiastic scheme. The heart of the chiasmus is inversion, and this principle is built into the structure of the whole volume. Over many poems, section one, “Preacher’s Daughter”, is inverted by section two, “Why the Groundhog Fears Her Shadow” which makes a shift to the feminine. Here we have moved out of the booming and amorphous province of the sky father that leaves no place for a female to stand. We are now in an earthy place, a burrowed, homely, hidden arena, the cave of imagination gestating. This is the transformative locus where the leaden dross of childhood is transformed, in each of us, into the golden nuggets of understood experience that make us the individuals we seek to be. This is where the mixed directives are alloyed, where the shattered psyche is annealed. Section three restates this in prose and (significantly) in couplets. This reprise in the third section, prose studded with couplets, titled with deliberate deployment of the shift key, “THE CASTLE OF EITHER/OR: a fairy tale” is another way to capture and state the dialectics at work between daughter-poet/father-preacher and all the attendant cultural echoes.

True progress requires revisiting the past and understanding it in a new light before it is possible to move truly forward. Without this often uncomfortable but essential step, one has the delusion of progress while remaining lost in the wilderness, wandering in circles.

Arriving at Synthesis—New (if, perhaps, temporary) Wholeness

From the first epigraph to the title of the last section to the dramatic situation of the last poem, Haymon is angling toward healing the deep division that the volume as a whole charts. The cartography of fracture Haymon delineates is one of grief and separation, but readers always feel not only the anger but also the yearning to bridge the engulfing splits between speech and silence, male and female, spiritual and physical, ideal and actual. The poet-daughter comes to wholeness, which is, I believe, the aim and right function of religious practice. She does not know if her departed father has the vision now to see this and approve, whether he is proud of her accomplishments, poetic and personal. Ultimately, Haymon discovers, that is immaterial.

The collection’s structure emphasizes both the divides that must be crossed and the essential unity that underlies those divisions. “Continental Divide”, for example, opens the concluding section of the volume. This section of twenty pages, entitled “Daughter’s Fealty”, provides a necessary resolution to the suffering delineated in the previous fifty-five pages, a hard-won denouement.

The collection as a whole documents in poetry this underworld journey towards recovery of psychic wholeness in the light of personal truth and personal voice. There is rage, but there is also tenderness. With real names and biographical details embedded a textual signposts throughout the work, we are invited to understand that the conventional mask of the persona, the “speaker of the poem” rather than the poet herself, is gossamer thin if it exists at all. If this leap is uncomfortable for the reader at times (and it was for this reader), how much more so must it be for the poet? I see this fusion of poetic technique and control with explosive (apparently) biographical material as a courageous and necessary one. Indeed, it is difficult to see how Haymon could achieve her aim of breaking past enjoined silence without creating this book’s hybrid of memoir, lyricism, and mythological journey toward psychic wholeness, which requires de-mythologizing the father and the whole patriarchal system of fundamentalist Christianity. Though Haymon’s work calls to mind the “Daddy” and “Daddy-Husband” poems of Sylvia Plath’s The Colossus, Crossing the Water, and Ariel, her intention and strategy is the polar opposite: rather than mythologizing herself or her father, rather than elevating or inflating her confusion, suffering, or woundedness, Haymon uses all her poetic gifts to contain and shape the pain, to reduce the power that memories of betrayal and shame often have, and to speak personal truth compellingly but without hyperbole.

The weaving together of the quotidian world, the deep roots of memory, lyrically inflected visitations of spiritual vision, and popular culture are all present in the details she selects in the first section of “Roundball” in which she details the circumstances of her father’s death. Divided as they are in so many ways, at the moment of his death they are watching the same basketball game—she in person with her son, he on a television set in another state. The poem is a multi-sectioned and many-layered working out of the strands outlined above. Consider this portion from the first section and what she achieves with it:

"My father died watching

the LSU-Georgia basketball game. Watched it

on his homemade TV in Leland, my mother

fixing supper in the next room.

I was in the Assembly Center

in Baton Rouge, so in a way

you could say I was there when it happened.

My son’s braces came apart in the 2nd half

when he chewed ice from his coke

—I stared in my palm where he spit

the wires and metal bands. They shone white

in TV floodlights that cast no shadow—

I saw right through my hand.”

On the surface, there is the matter-of-fact account of what seem to be straight-forward details. Haymon has turned them beautifully to account. The divisions—two genders, two generations, two different states, two different ways of watching, two states of being (life and death)—are accentuated as is the unity despite the divisions.

The poet-daughter is under the TV lights while the preacher is watching on a TV he created; the poet is focused on her role as a parent, receiving spit and a broken tangle of wires in her hand; the maternal moment causes her to look away from the game and gives her a moment of x-ray-clear vision, while the preacher-father, exiting life, enters a vision of his own, a kind of fusion with his younger, pre-parental self, before his failures, his sins against God, nature, and the poet. They are both playing the game of life, but in different ways, on their own terms.

This elegiac but never sentimental poem, characteristic of the resolving fourth section, signals Haymon’s public, posthumous message to her father: the preacher’s daughter is loyal to both his memory and to the truth, to examining received truth. More broadly, I think, it implies hope for reconciliation for humanity, that the twin struggles for individuation and clarity about the past are no fool’s errands but primal, essential, and will be crowned with success.

Conclusion: Full Spiral

Eldest Daughter is the achievement of a mature vision. Using her poetic gifts, Haymon bears witness to an open secret, a hideous truth beautified by poetic music but nonetheless unearthed and now bald-faced and revealed. Her disclosures name personal violations from her father and point to the collusion of the entire patriarchal system and the tradition of Southern Baptist preaching and preachers. Haymon’s techniques, as well as her individual poems, remind me strongly of the scissored lacework silhouettes that form the recent body of work by African American visual artist Kara Walker. Walker uses her intricate, painstaking skill to expose the abuses of the system of plantation slave-holding that subjected people of African descent to vast injustices. Haymon uses intricately wrought language to expose abuses of power within a particular family and, by extension, within the extended communities of the congregation, the Christian church, and western-derived patriarchy.

Significantly the collection ends with an image of qualified communion between father and daughter. In “My Father Will Have Two Dozen on the Halfshell”, Haymon weds allusions to classical, Shakespearian, and modern literature with Biblical proverbial wisdom within a frame of matter-of-fact narrative. Over the same restaurant dinner of oysters, each brings memories, assumptions, skills, and desires to the table. The slippery and dangerous work of opening the oysters—legendary aphrodisiacs hauled from “beds” briny, cloudy, and deep—engage them both but in different ways. The father, laconic, is also diminished from previous monstrous proportions. At this last shared table, the daughter places the order; her voice is dominant, the one with the power and distinctly female. From this place of power, she makes the choice not to speak to the father who cannot truly acknowledge or hear her, not to cast her pearls before swine. Rather, she speaks to us.

The daughter-speaker understands that their visions, even of oyster beds as with everything else in this world and out of it, will always divide them despite the ties that bind them. He dreams of the “ cold Atlantic bitterness”, of waters farther north where he was formed, “…fresh from seminary, before he failed….” The word failure rings out on many levels: the reader hears not only failure of health but of courage and humanity, not only of professional failures but personal hypocrisy and the corrosive failure to live up to his own principles and ideals. She dreams of the warm “milky” waters of the Gulf of Mexico where she was raised, and concludes, with echoes of both Shakespeare and Plath: “…I’d see/pearls, spilling from his mouth like a god’s.” Again, with the techniques of inversion and revision of received wisdom, Haymon refuses to allow the swinish father to trample her own pearls of wisdom. Simultaneously, she acknowledges that her father is a primal source of her now-gathered power: his example and his crime against her have supplied the irritant that manufactures pearl after pearl of poetic encapsulation of pain. Her own poems are raised up out of the murky sea bed of childhood experiences, prised out of their shells of silence by a muscular effort of will, and labored into existence. Finally, reflecting but standing apart from these two parents, the poet and the preacher, the poems themselves are what command our attention.

In Shakespeare’s last play, the sea-misted work of The Tempest, the action is initiated by family betrayal and healed by wisdom, magic, and poetry for the next generation. The setting is the exile of a father and daughter on an unnatural and enchanted island. The action concludes when the power of the father is self-banished and the daughter’s center of gravity shifts from the father’s affections and schooling toward her own future. The father’s minion of spirit, Ariel, sings a famous song that concludes

Full fathom five thy father lies;

Of his bones are coral made;

Those are pearls that were his eyes:

Nothing of him that doth fade,

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.

Sea-nymphs hourly ring his knell….

In Plath’s referential 1958 poem, “Full Fathom Five”, the daughter-speaker opens:

Old man, you surface seldom.

Then you come in with the tide’s coming

When the seas wash cold, foam-…

and ends with

You defy questions;

You defy other godhood.

I walk dry on your kingdom’s border

Exiled to no good.

Your shelled bed I remember.

Father, your thick air is murderous.

I would breath water

The father in the last poem of Eldest Daughter is not God and no longer a spokesman for spirit, but he is a progenitor and (perversely) a fountain (or font) of poetry; if his baptismal font has run dry, the wellspring of her poetry has not. The last poem of the collection earns its measure of peace and reconciliation from a past that cannot be changed but can be used to create art, that lever capable of moving away a world of pain, of opening a door to a new understanding of personal authority. In this last-described, posthumously recalled supper the image of the preacher, the father once conflated with God—clay feet under the table, fumbling with his dinner—wanes. His poet-daughter now orders events, as the title of this poem makes clear. She also gets the last word. This is the end of the journey from her southern Baptist childhood invoked in the first poem of the collection. Here at last I truly believe her, despite her irony, when she says that she is grateful for that confusing and painful childhood.

Like Plath, Haymon writes to exorcise the demon that haunts her imagination, but unlike Plath, Haymon completes the task. These poems, burnished over many years, chart the journey she has made down into the darkest rage—the making dark of the Earth itself—and back up toward the daylight, carrying the healing, annealing qualities of the country of shadow with her. In the end, the fealty that this mature daughter-poet-mother expresses is toward the truth, toward the life she is yet to live, the poems she is yet to write.

Eldest Daughter is a bravura performance by a poet of great depth. We can only anticipate Ava Leavell Haymon’s next book.