Half-Moon Set

for William Shakespeare

I Oxford English Dictionary

Sir James Murray, caught fast in webs of word,

sought the earliest spinners of our pages.

You, Will, our most daring, can still be heard

in hundreds of words you gave to the ages.

I recall that long table holding green,

heavy volumes in the main library

where I first pondered: What did Falstaff mean

by “dwindle?” In tiny print, the O.E.D.

cited you as coiner. From Scottish, “dwine,”

(“to waste away, to fade”) you gave a twist,

conjoined it to “kindle,” and made new wine

with a flick of your vintage plume, your wrist.

Thank you for “Zany.” “Green-eyed.” “Howl.” “Moonbeam.”

“Grief-shot.” “Honey-tongued.” “Madcap.” And “academe.”

II Tinkerer’s Damn

Sometimes it’s finding the right word. Sometimes

it’s making it. Fit an old stem with ends

we know. Solder nouns onto bright verbs. Rhymes

and rhythm and thought give old words twists and bends

with ease. They please us, these shiny new toys

cobbled and seamed, buckets and kettles sturdy

yet handy, able to transport vast joys,

woes, or curses without being wordy.

In this sublunary world, can we know

where perfection exists or if we make it?

Poets, anyhow, keep tinkering under moonglow,

willing to be fooled, or to fool, or to fake it.

Our half-dark, half-light moon—inconstant sphere—

urges whatever it takes to make things clear.

Leslie Schultz

Yesterday, a friend asked me what makes a poem a poem, and I could think only of partial answers to that keen question. This morning, I was lucky enough to be awake when the half-moon set in the early hours of one of the high holidays on my calendar, Shakespeare’s birthday, so I am thinking about what I have received from Shakespeare’s poetry–and, by that, I mean all of his inventive language whether crafted in sonnets or for the stage. I realize that it is the exhilaration of his verbal dexterity (marrying sound and sense with flair) and his daring in creating new (or new-ish) words when the one he wanted did not exist…His converting, disconcerting, diverting achievements–at the level of one word at a time–in service of the sonnet, the scene, or the play. That inventiveness gives us all new raw material and new license to dismantle and reassemble language.

We can’t know exactly which late April day on which William Shakespeare was born in 1564, only that it was near and before the recorded day of his baptism on April 26. (Since he died on April 23, 1616 there is a fitting symmetry in celebrating his birth on April 23–a kind of calendrical couplet encapsulating the shape of his work and life, like the way he chose to conclude the sonnets he wrought.) Similarly, we cannot know exactly how many words he invented on the spot and how many he simply seized on, used effectively and memorably, and is now credited as their coiner. Even conservative estimators, though, acknowledge more than one thousand “neologisms.”

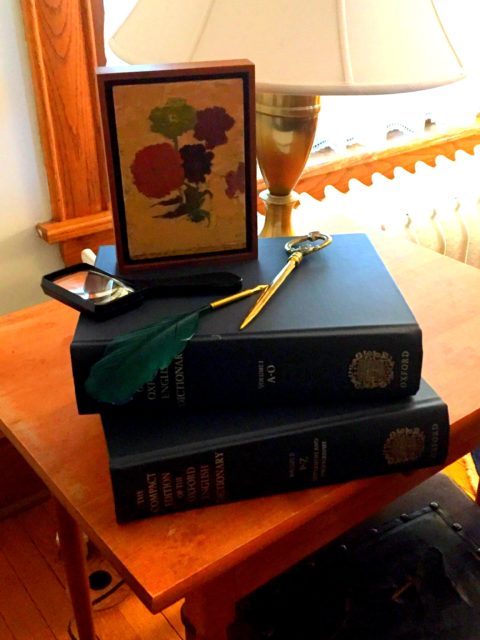

I learned the term “neologism” during a magical undergraduate year when I studied Shakespeare’s canon at the University of Wisconsin under Professor Standish Henning. He directed students through the portals of Memorial Library, past the carved dictum, “The truth will set you free,” and into the Reference Room toward the incomparable resource of the Oxford English Dictionary. (As soon as I could afford it, after graduate school, I purchased my own copy of the condensed print version, complete with magnifying glass.– I didn’t used to need that, but now it comes in handy!–and I have yet to fulfill my intention of acquiring a copy of Caught in the Web of Words, the biography of Sir James Murray, chief editor of the Oxford English Dictionary,by his granddaughter, K.M. Elizabeth Murray, but it is comforting to know that pleasure shimmers before me.)

Coming back to my friend’s question, I think the essence rests in the desire to make something new, to enrich the given language in some way. “Poet,” I understand, comes from the Greek word for “Maker.” I know I am inspired by what I have read and heard–surely millions of words–and by such delightful local twists as Northfield’s Sidewalk Poetry motto “Make Your Mark” and Paula Grandquist’s coinage for the name of her show on KYMN, “ArtZany.” (Tune in this Friday at 9:00 a.m., by the way, to hear Paula talk with this year’s winning poets and hear them read their work–or find it on the KYMN online archive after Friday, April 27, 2018.)

What do you think? What is the essence of poetry? How do you know something is a poem? Have you recently invented a word or phrase? Is there one you wish you had? (I wish I could take credit for “Snafu,” “Kludge,” and “Glitch.”)

As Paula says, “Enjoy your imagination today.” Best, Leslie Schultz

Check out other participants in the NaPoWriMo Challenge!

I love your definition!

What a post, Leslie! Didn’t know that about dwindle or so many words you spotlight! The whole post is fascinating – including knowing a few things about you I didn’t.

Poem to me? Hmmm The most beautiful form of compression to the essence of something.

Dear Julia,

Thank you for checking on this. I do find a couple of images to hold interesting parallels, questions of influence aside. (As you know, Yeats is one of my very favorite poets, whose work I memorize as I can.) I will listen with great interest, too, to the link you send via email.

How happy I am–how enriched I feel–to have friends like you who care about poetry so deeply. Leslie

Leslie, I checked, and it seems that Yeats was not well-known in Russia during his lifetime, though Pasternak may have known his poems in the 1920s. As we can’t talk about the influences in this case, the scholars usually consider Pasternak’s poetry (and works by other poets of his generations) as parallel to Yeats’. I liked it how Yeats was “explained” and compared to Pasternak in one literature textbook, which made it easier to understand him.

Pasternak’s translations of Shakespeare are masterpieces of their own. He worked on “Hamlet” for 30 years, and this is the translation that has been used in theater productions and films. There is probably more of Pasternak in this “Hamlet” than in ordinary translations, but the lines stay with you forever.

Julia,

Thank you so much for this marvelous and thoughtful (and thought-provoking) response. I hope a lot of people will see this.

I love the poem by Pasternak, its lyrical manifesto for poetry. It reminds me in a few places of works of Yeats, but is also wholly new. (Did Pasternak like the work of Yeats, I wonder?)

It is a wonderful cultural heritage to have lines of poetry as touchstones that unite strangers. Some to aspire to here, though not, I suspect, attainable in my lifetime.

In gratitude, Leslie

Leslie, the Russian culture is locked on poetry. It is our common language. You could use a line of any great Russian poem to establish a connection with a stranger. It is the culture where President every year reads a poem to congratulate women with the International Women’s Day on March 8.

Each major Russian poet has a poem or two on the meaning of poetry. Pushkin’s “The Monument”, Mandelstam’s “Silentium”, Akhmatova’s “About Poems,” and Pasternak’s “The Definition of Poetry” come to mind first, but I found thousands of others. Poetry is “the world observed through the prism of inspiration” for Valery Briusov, “a thought tripled in its body” for Zabolotsky, and “a barrel full of dynamite” for Mayakovsky. Mayakovsky wrote a poem titled “A Conversation with a Taxman about Poetry”. How about that?

For me, the phonetic and stylistic aspects of the poetry matter most. Here is a translation of one of my favorite poems by Boris Pasternak written in 1956 (the translation by Natasha Gotskaya (2010) is not perfect, but it tries to catch the rhythm; “lime trees” is British for “lindens”):

In every thing I want to grasp

Its very core.

In work, in searching for the path,

In heart’s uproar.

To see the essence of my days,

In every minute

To see its cause, its root, its base,

Its sacred meaning.

Perceiving constantly the hidden

Thread of fate

To live, to think, to love, to feel

And to create.

If I was able, I would write,

I’d try to fashion

The eight of lines, the eight of rhymes

On laws of passion,

On the unlawfulness and sins,

On runs and chases,

On palms and elbows, sudden somethings,

Chances, mazes.

I’d learn the passion’s rules and ways,

Its source and matter,

I would repeat its lovely names,

Each single letter.

I’d plant a verse as park to grow.

In verbs and nouns

Lime-trees would blossom in a row,

Aligning crowns.

I’d bring to verses scents and forms

Of mint and roses,

Spring meadows, bursts of thunderstorms,

Hay stacks and mosses.

This way Chopin in the old days

Composed, infusing

The breath of parks and groves and graves

Into his music.

The triumph – agony and play –

The top, the brink.

The tightened bow-string vibrates –

The living string.

A word-by-word translation is available here: http://max.mmlc.northwestern.edu/mdenner/Demo/texts/in_everything_reach.html

Sorry that it is so long!