Since just before Julia was born, I have been more interested in genealogy. I am now convinced of the importance of writing down the memories I have and the stories I hear. (Like Herodotus, father of history, I think it is important to write them down whether they can be verified or not.)

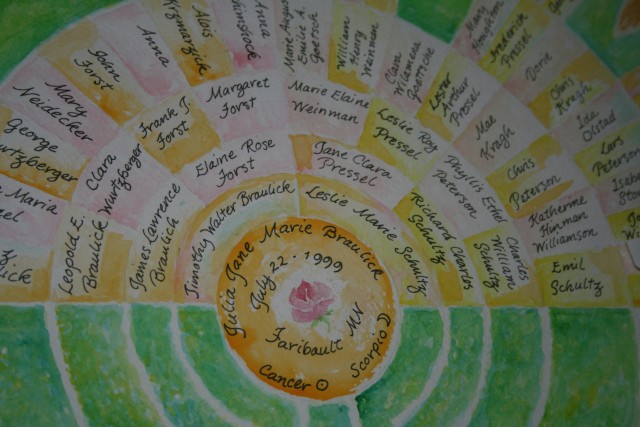

When Julia was a baby, I started gathering information to create a family tree–or, perhaps more accurately, a “tree of progenitors”, since the information doesn’t include brothers, sisters, cousins, additional marriages, and so on. Instead of Julia being situated as a leaf on a family tree, she is the locus around which her direct ancestors are arranged in the symmetrical fashion of a Palladian window, retreating in algorhythmic progression as far as we have information. Just before Julia was born, I asked an artist friend, Marilyn Larson, to write in the names in her beautiful handwriting. As you can see below, she did much more, creating a design that incorporated watercolors of our labyrinth and objects from our home and life (wild roses; the Bear Paw quilt I made for my sister; Ursa Major; and our dog, Luna.)

Tim’s family is on the left, mine is on the right. They march back symmetrically through the generations: 2 parents, 4 grand-parents, 8 great-grandparents, 16 great-great-grandparents, and so on. Some lines are much shorter than others: they exist but cannot be known since we have nothing written down. That gives me a chill. Why? I am quite sure that these people were full of fears and desires, laughter, heartache, and achievement. Yet just a few generations later, they are smoke. Poof! Gone. Passion for living spent. Not even a name remaining.

Well, for my great-grandmothers,(Julia’s great-great-grandmothers) we do have the names, even a few memories and stories. I have remembered and gathered and written down what I could. Over the next four Wednesdays, I am making one post each for four very different women, each of whom is my great-grandmother. The personalities and available information for each also differs significantly. I don’t know why, but I am convinced that it is important to document this family members in all their warty, beautiful humanity, beginning with my father’s mother’s mother.

QUARTET OF QUEENS

So far as we know, we don’t choose our relatives. We work with the hand we are dealt, because we can’t fold. Time and distance makes it easier to see the ties that link us to those who lived long ago and share our genes if not our memories or dreams. I don’t claim to see myself or my parents objectively. Even my grandparents are a bit too close for that. But, somehow, the great-grandmothers are distant enough for inspection, yet close enough for a felt connection.

MAE

My father’s grandmother, Mae Kragh Peterson Danielsen, grew up on a farm outside Weyawega, Wisconsin. She was fiercely ambitious and wanted to live away from the dirt, the stench, the unrelenting work that farm life entailed. Mae was very beautiful in her youth, with a long, white neck, blonde hair, and eyes as blue and cold as the Baltic sea.

When this full-blooded Dane married early, she left farm life in the dust as soon as she could. She whipped her gentle alcoholic husband, Chrissy (another Dane), into town, much as she would a slow horse. Eventually, he would bolt, and they divorced. My grandmother, Phyllis, cried that one time when I asked her to tell me about her mother. Mae moved the family to Appleton, Wisconsin during the roaring twenties.

Mae was restless, active, and shrewd. In time, she grew moderately rich on city real estate. Below is a photo of the last house she occupied, on Loraine Court. I remember the house better than I do her, because it was just a few blocks from my high school, and during my last year of high school it was the home of my Grandma Phyllis, Grandpa Charles, and my aunt, Debbie.

In her prime, I was told, still married to Chrissy, she enjoyed the company of other men. When found out by her adolescent daughter, Mae bought Phyllis expensive clothes and long, elegant, pointed shoes to ‘keep her mouth shut,’ Grandma told me.

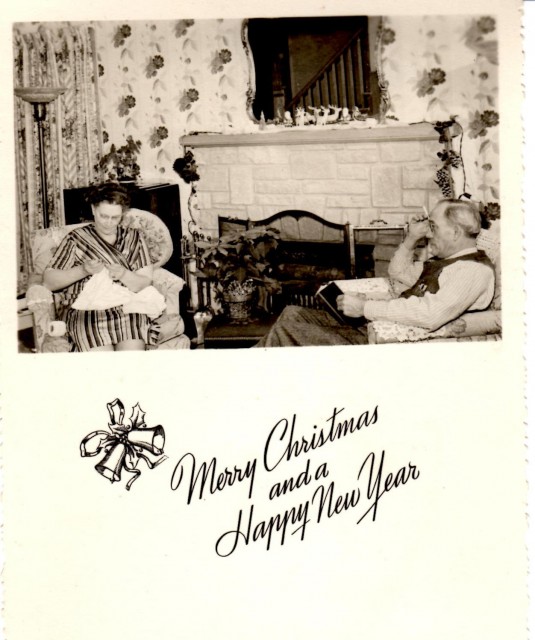

Mae used her beauty as a weapon, and she had other weapons, too, everything from a tone of voice to the back of a hand. People said (after Chrissy) she’d have to find a saint to marry her. They also said that she’d found him in Jim Danielson. Gentle Grandpa Jim had come from Denmark as a young man to work as a lumberjack in the Big Woods of northern Wisconsin. Six decades later, he kept the music of his mother tongue, even as he spoke English with great courtesy. Because he lived until I was in high school, I have more memories of him. I also have his axe. It resembles the form I remember him having: long and slender, silver-headed. Jim and Mae married when she was already a grandmother, but he was the grandfather my own father knew and loved.

Of all my great-grandmothers, my memories of Mae are the strongest. I can’t recall her speaking to me, but I remember her agitation, her wall-to-wall wool carpets the color of liver, her flaky pie crust, her fragile Danish dishes and how particular she was about how they were washed and dried. I remember family dinners at which she presided: the food flavorful and all those gathered for dinner slightly afraid of her. Her face in old age grew pointed and thin, like the face of the mink Grandma Phyllis wore clipped around her shoulders on Sundays. I have Mae’s blue oval wool tablecloth with the short fringe, the wrong shape for my table. I also have photos of her that fascinate me.

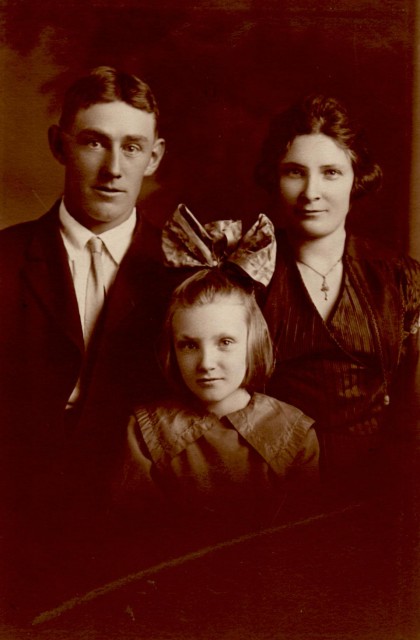

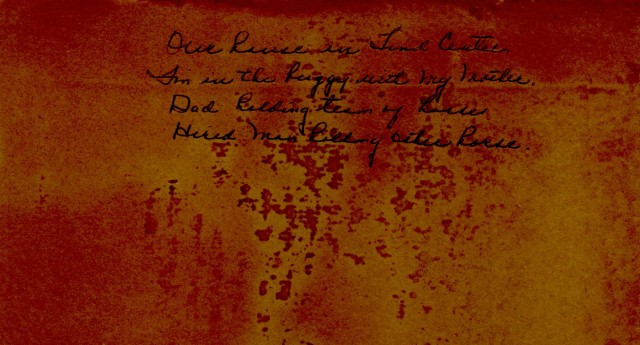

In the first, she is a small figure, barely distinguished, yet somehow a focal point. She stands away from the farm that is now dust, outside little Lind Center, Wisconsin. The farm and the town, too, have disappeared from the maps. There are two men, a team of horses hitched to a wagon, a farmhouse. Mae stands holding the handle of a baby stroller in which my grandmother, Phyllis, sits.

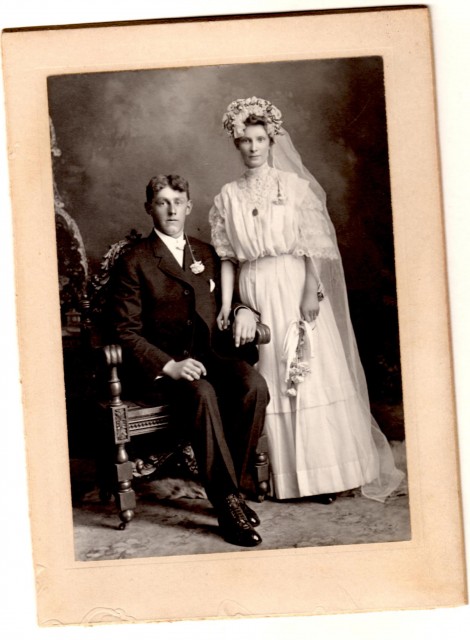

Another was taken the day of her wedding to her first husband, Chrissy. He looks stunned, his hair parted as though with a hatchet. He sits, while she stands behind him. Long-stemmed carnations are pinned to the lace at the shoulder of her dress, upside down, as though they are hung up to dry.

The last photo is close-up of her face. She is in her 50s, long before I knew her, but about the age I am now. She has heavy jowls, red lips, the intent focus of a predator about to pounce. Her smile unnerves me so much I hide her picture even now.

I have heard how Grandma Phyllis would drive to see her, a journey of six hours. In the last hour, near Fond du Lac, about sixty miles from Appleton, Phyllis would begin to chain smoke. You never knew just when or how Mae would strike. Mae was famous for her lemon pie, a light golden crust and a sour bite under the sweet.

The story I can’t forget is how, once–finally–when Mae lifted a hairbrush against her four-year-old granddaughter, Debbie, in a sudden spat of anger, Phyllis finally spoke up. Catching her mother’s wrist in mid-swing, Phyllis said in a low growl, “If you even touch my daughter, I’ll break your arm.”

When I think about this, and when I look at these photographs, I am reminded that determination is a powerful force for either good or ill. I understand the appeal of fine bones, fine looks, fine clothes and china, but I can see, too, that finer feelings matter more to me. I also see that the stories that live on after us are only part of the truth, and that we influence–but do not control–which ones are told of us, over and over, out of our hearing.

Finally, I see how family stories connect us with the past, and how history itself is a tangle of the family stories we all share.

Thank you for reading this! If you think of someone else who might enjoy it, please forward it to them. And, if you are not already a subscriber, I invite you to subscribe to the Wednesday posts I am sending out each week–it’s easy, it’s free, and I won’t share your address with anyone!

Thank you for reading this! If you think of someone else who might enjoy it, please forward it to them. And, if you are not already a subscriber, I invite you to subscribe to the Wednesday posts I am sending out each week–it’s easy, it’s free, and I won’t share your address with anyone!