When I was a little girl, my best friend, Brenda, lived on an Oregon hobby farm. Some of my happiest memories of that time include picking blueberries and gooseberries from her bushes, climbing up to the hayloft, drinking homemade root beer (bottled in recycled beer bottles) unearthed from a dark cellar, and, after watching television coverage of the Moon landing in 1969, going out into the pasture to look up at the sky and imagine people up there. (Coincidentally,that was exactly fifty-one years ago today!) My time with Brenda and my voracious reading of the Laura Ingalls Wilder books made me yearn to live on a farm–something I have never done.

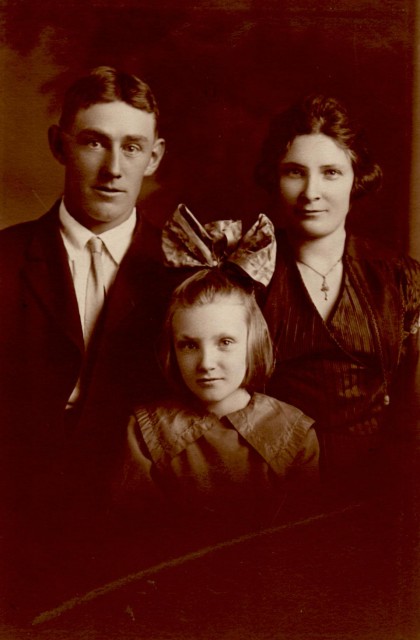

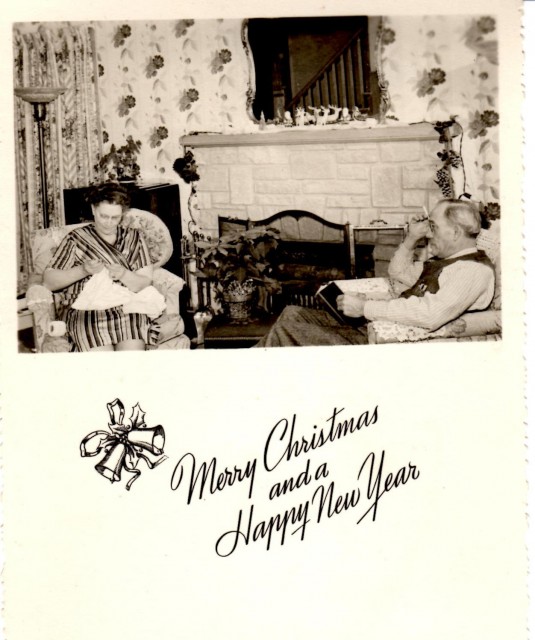

In the 1980s, though, I was lucky to get to know Tim’s family and two Minnesota farms: Red Oaks Farm (later Linden Acres) where my in-laws moved to one their wedding day, and Mohr Century Farm, where my sister-in-law, Marea farmed with her husband, Myron.

In the 1990s, a regular part of my work as a freelance writer was for The Bush Foundation of Saint Paul, and one part of that assignment was working with those given fellowships by the Foundation. John Hildebrand was a 1994 Bush Artist Fellow, and (though I can’t quite recall now) I believe that that is how I became aware of this book that I first read in 1995 and haven’t stopped thinking about since.

I have written very few reviews in my career, but this book simply required me to make the effort. I was delighted when the Northfield News agreed to print it, and I hope that this republishing of my own review, if it succeeds in enticing you, will lead you to other reviews and to the rewarding experience of reading the book itself. (Northfield readers: I just checked, and the Northfield Public Library has it in its excellent collection! It has also been republished by the Minnesota Historical Society Press and is available in their online shop.)

Certainly, in the intervening decades since Hildebrand’s work was published, farming has continued to evolve and change. What surprises me is how much of his observations seem so current twenty-five years later.

Below is my original review as it appeared on October 13, 1995 in the Fall Harvest Edition of The Northfield News, with sub-heads added by the editor.

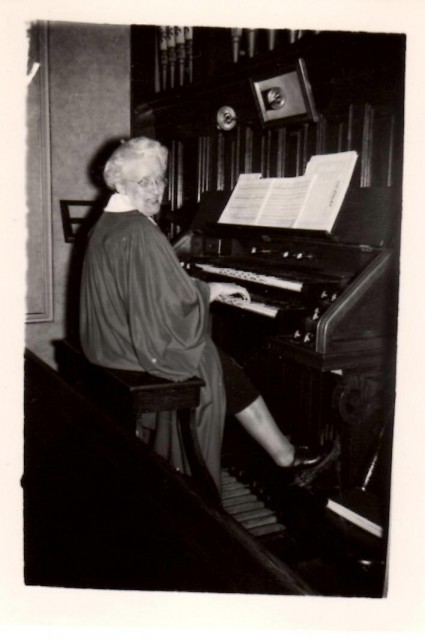

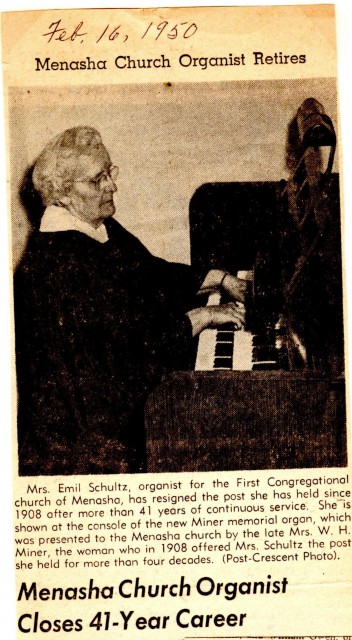

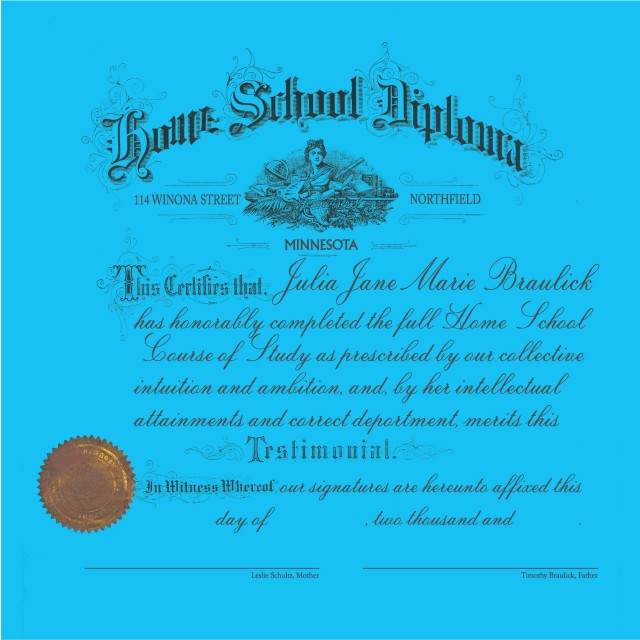

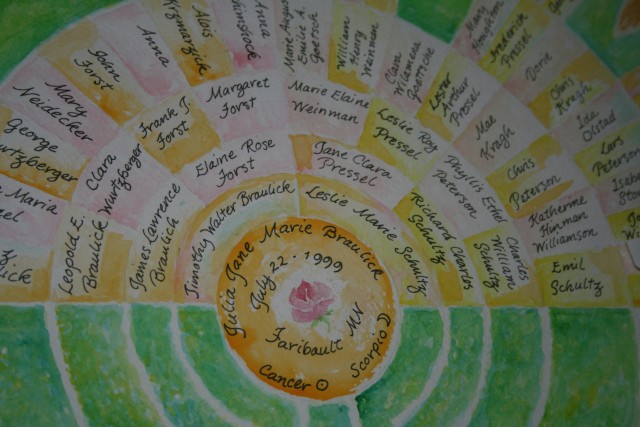

Mapping the Farm: The Chronicle of a Family by John Hildebrand (Alfred A. Knopf, New York, NY 1995) reviewed by Leslie Schultz

An adventure? A documentary? An elegy? A love story? Mapping the Farm could be considered all of these as it chronicles the intersection between an Irish immigrant family and a 240-acre plot of land outside of Rochester, Minnesota. When I spoke with him by phone, John Hildebrand managed to condense his multi-layered work of non-fiction into a neat paragraph:

“I see this as a companion piece to Reading the River, a travel book I did about the Yukon. There, I traveled horizontally through space. Here, I go vertically through time, back to the potato famine in Ireland which brought my wife’s family, the O’Neills, to their farm four generations ago. Farms all look the same from the highway, but I have found each to be a separate kingdom, complete with its own topography, history, and mythology. I worry that these little countries, which hold families together, are disappearing fast

Hildebrand’s point of view in this is poised between the objectivity possible to an outsider and the passion and intimate knowledge that comes only over time to an insider — in this case, the clear-eyed son-in-law who gets a kick out of driving the tractor. This biography of place manages to be both precise and imaginative as it explores the ways in which a family and a piece of land have shaped each other. By placing the story of one family of farmers within the larger social and political contexts of each era — from the Irish troubles of the 1870s to the Great Depression to the farm crisis of the 1980s — Hildebrand shows how history continues to be made locally.

Keen metaphors

Despite the depth and breadth of this work, it is neither dry nor scholarly. Throughout, the prose is lyrical and studded with Hildrebrand’s keenly made metaphors and wry observations of himself, his in-laws, and the local culture. Perhaps it is most poetic when he simply describes the details of daily life and of the portraits, platte maps, and aerial photographs that are the viewing stations for the panorama he surveys. Then the physical details and their juxtaposition allow the mute but innate symbolism of nature and relics to emerge with true eloquence. Fact and the framing of it create a lyrical overlap on every page. Like Ireland’s Seamus Heaney or America’s Annie Dillard, Hildebrand knows that true music lies in the names of things

He also knows how to tell a story, weaving multiple timelines together with facility. Each chapter begins in the present, then moves naturally and anecdotally into the past. The cumulative effect is four-dimensional. Using these various strategies, Hildebrand describes precise coordinates of time and space, heart and mind.

Farm mythology

The mythology of the farm begins with the old Irish story of the Red Hand of O’Neill. As Hildebrand tells it, “As a fleet of longboats neared the Irish coast, the invaders engaged in a race, having agreed that whoever touched the land first would be its ruler. Whereupon a certain O’Neill drew his sword, lopped off his own right hand, and flung it ashore. The story was apocryphal, but nicely illustrates the lengths to which an Irishman will go for a bit of land.” On American soil, the Catholic liturgy, refracted through the agricultural year from the small rural church of St. Bridget’s, where the foregone O’Neills lie buried, provides a continued sense of mythic undertaking.

The detailing of topography ranges from early surveyors to the local names that have emerged over time. Take, for example, the genesis of the orchard: “Apple trees were the blaze marks of civilization. Government surveyors laying out [President Thomas] Jefferson’s grid upon the prairie often planted apple seeds to mark the section lines, knowing the settlers to follow could distinguish an apple tree from a wild plum or a thornapple.” The orchard, “one of those half-wild places where the intentions of people and nature overlap,” is just across the lane from the Night Pasture, whose name conjures images of cattle drowsing under sunsets, crescent moons, and shooting stars.

Living history

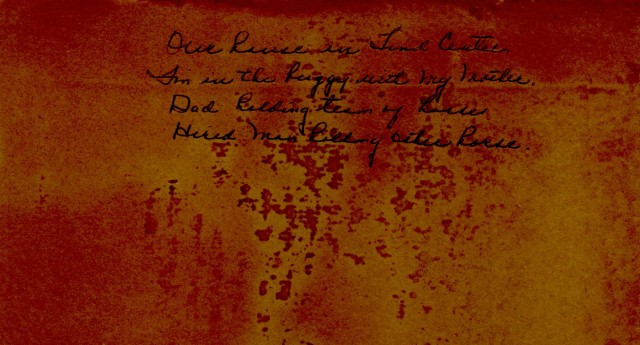

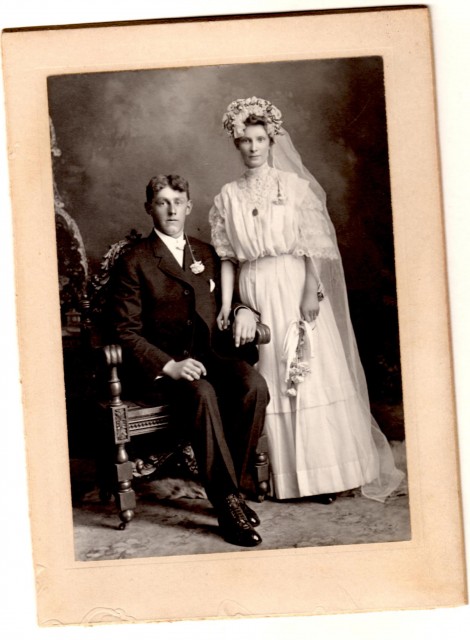

History — personal, political, and philosophical — is made to live and breathe. Hildebrand recaps the brief journey in 1861 to Minnesota of Henry David Thoreau, a philosopher who took note of what was soon to be trampled. He also relates the culture shock of the new immigrant. When Catherine Esmond, Sharon Hildebrand’s great-grandmother, decided to emigrate in order to better her circumstances, her relatives threw her an “American wake” because “the emigrant was traveling west, like the souls of the dead, and wasn’t expected to return.” Arriving to work as a domestic servant in Philadelphia, during a tide of mick-hating that lasted until the Civil War, Catherine married Gettysburg veteran William O’Neill and became a farm wife. Upon his death in 1887, Catherine ran the rented farm, using as a point of reference How to Make the Farm Pay, which stated in its preface, “What has always been claimed by a few, will soon be acknowledged by all, that the prosperity of a country depends upon the intelligent cultivation of the soil.” In her old age, with the help of her sister, Catherine was able to buy the farm she had rented for so long.

Past and future

If the O’Neill farm proves a gateway into the past, it is the land around it that shows the future — the subdivisions mushrooming across Highway 52, bringing the city of Rochester ever closer. A distinctly elegiac tone suffuses this work, the “songs of a rural diaspora.” As Hildebrand reminds us: “the anonymity of farmland is what makes it so easily converted to other purposes.” He points out “the hilltop houses are of the multi-leveled, many-square-feet, awesome-garage, LOOK-AT-ME school of architecture.” These are “houses that solve the problem of how to live in the country without living in the country. Houses that would seem even more hideous if some of them didn’t belong to the sons and daughters of those who once owned the pasture.”

All in the family

In explaining the concerns of his in-laws, Ed and Fran O’Neill, about making estate plans to ensure that the land, now coveted by developers, remains in the family, his words go beyond the fate of one family. “The state of Minnesota recently decided to close its agricultural research center at Waseca and convert it into a prison because corrections has turned into the kind of growth industry that farming isn’t. If this farm is lost, it won’t be because of crooked bankers or poor markets or even bad luck. It will be a failure from within when, after four generations on the land, the line of descent finally runs out.” He further notes, “Land itself can never be lost, only transformed; what is slipping away, day by day, is the meaning that connects us to it.”

Although there are eight O’Neill children who all pitch in when they can, none is in a position to catch the passed torch and run the farm full-time. Instead, ownership has been gifted to all eight equally while the parents retain a life interest in the estate. This arrangement, which has a counterpart in my own husband’s family, amounts to “a postponement of hard decisions to come,” since “eight people can’t run such an intimate business as a farm.”

Nonetheless, however precarious the future, Mapping the Farm serves as a both a kind of a castle wall to the kingdom of the family farm and as a lifeline into the past lived by millions of Americans. As he observes of the effect of fencing, ” Leave a fence long enough, and a line of trees will grown along it. Like an ocean reef, a fence provides a foothold for plants and animals that would not otherwise survive the monoculture of cropland.” So, too, with naming what is loved and therefore beautiful. In the lines of this work, Hildebrand has made certain that much of what has been lived unspoken will retain a foothold.

John Hildebrand is the author of Reading the River: A Voyage Down the Yukon. He lives in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, and teaches at the University of Wisconsin. Recently, he was awarded a 1995 Bush Artist Fellowship.

Leslie Schultz is a free-lance writer who lives in Minneapolis.