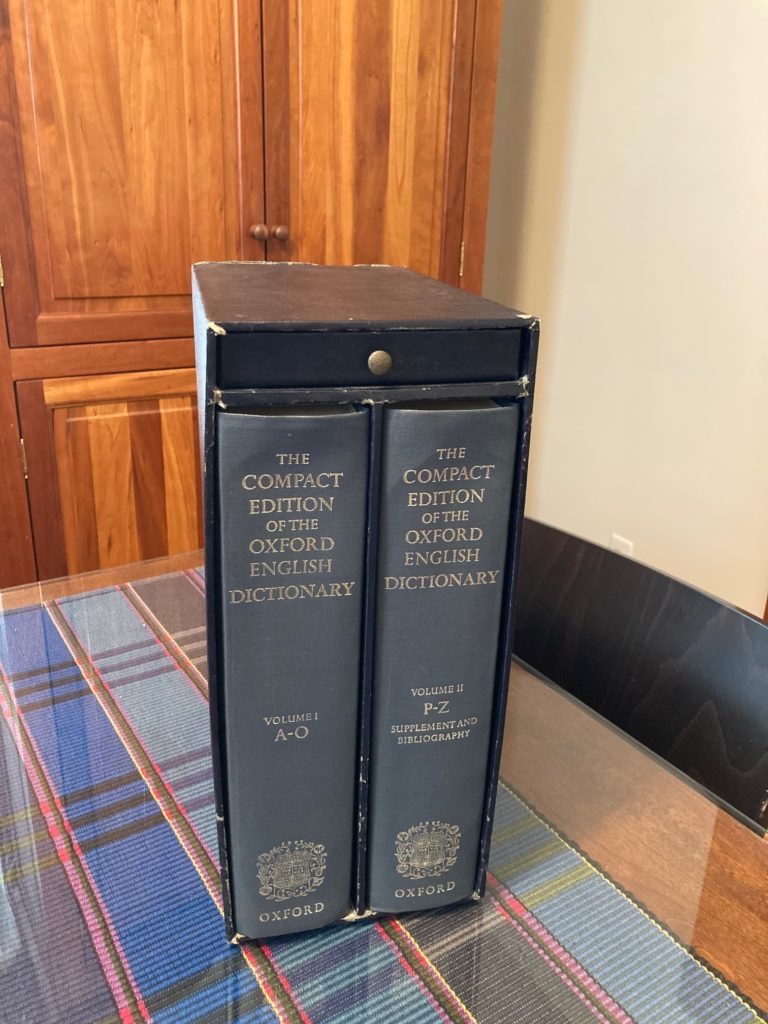

What English major doesn’t have a love affair with dictionaries? And the Oxford English Dictionary looms over all the others in terms of sheer size, scope, and audacity of conception. It was on this date in 1928 that the first edition of this lexical magnum opus was published. (For those who wish to revisit the story of how I first encountered this vast wordy edifice–and perhaps re-read the two sonnets I wrote in April of 2018 inspired by that encounter, click HERE.)

While the OED is the largest historical dictionary it is not by any means the first such project to trace the origins of a language through quotations. In fact, it is much younger than similarly constructed dictionaries in other languages (including Italian, French, Spanish, German, and Chinese) by, in some cases, centuries.

Initially, the plan was to create a dictionary that defined words left out of existing English dictionaries of the mid-19th century. When it was determined that such a supplemental volume would be far larger than standard dictionaries of the day, planning shifted to producing a new, comprehensive historical dictionary, and the leviathan project was concieved. A vast enterprise, it relied on professionals and an army of volunteers. It too twenty years to find a publisher, and another fifty years to complete the first edition.

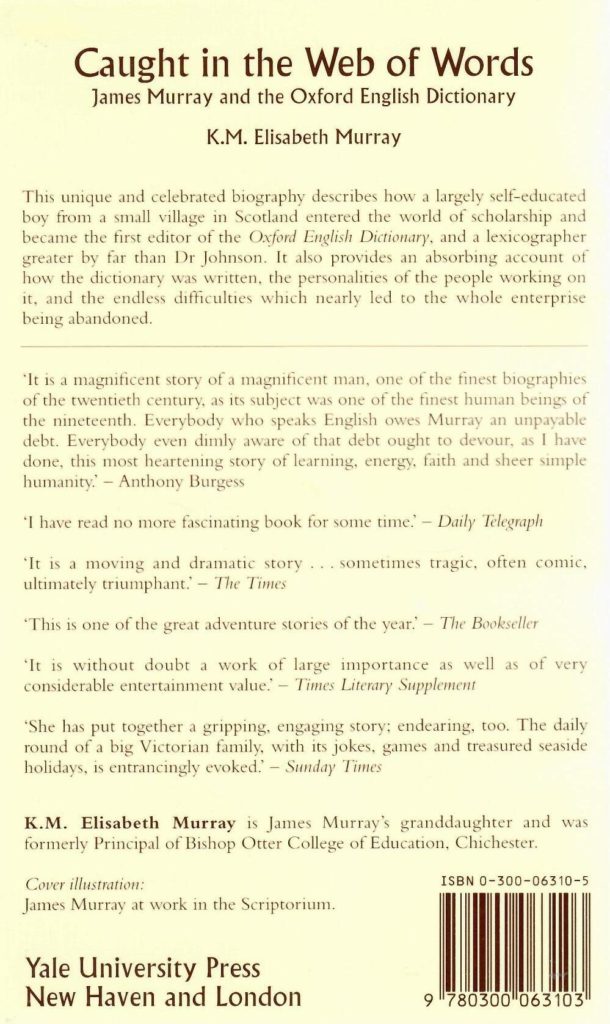

Want to know still more? Me, too. The history of The Oxford English Dictionary is well-documented. Two books new to my library are Caught in the Web of Words: James Murray and the Oxford English Dictionary by K.M. Elisabeth Murray (Yale University Press, 1977) and Treasure-House of the Language: The Living OED by Charlotte Brewer (Yale University Press, 2007). The first tells the heroic story of autodidact James Murray who helmed the project most of the way through the first edition, from 1887 until his death in 1915, and is written by his grand-daughter. The more recent book describes the ongoing efforts to enable the OED to keep pace with the English language as it continues to evolve.

In addition, in 2019, the dramatic story of the struggles to create the OED were dramatized in an effective (though intense) film presentation called “The Professor. and the Mad Man” starring Mel Gibson (as James Murray) and Sean Penn as one of the dictionaries most beset, troubling, and helpful volunteers.

Regarding the Poem “Kiwi”:

I first tasted a kiwi fruit when I was twelve, newly arrived in Australia (for what turned out to be a two-year sojourn.) This beautiful, pellucid, pale green fruit was set into the white of a dazzlingly white and light and sweet cloud of meringue and whipped cream called a Pavlova, perhaps the most popular summer dessert recipe star of women’s magazine pages (which I consumed avidly as a young teen there, along with other fluffy reading such as Barbara Cartland novels.)

Now I have a kiwi vine planted to the north of our front porch. It is beautiful, airy, sturdy, and even voracious. Every summer, we are compelled to get out the clippers so that it doesn’t consume the porch railings. Every few summers, now that I have a stand mixer, I whip egg whites and try to recapture the magic of that first bite of Pavlova (named by an Australian chef, it is said, in honor of prima ballerina Anna Pavlova’s visit Down Under in 1926, aiming to equal her legendary lightness.) Perhaps the kiwi vine, itself offer the better metaphor for Pavlova with its vaulting arabesques and reedy flexible toughness?

Until tomorrow,

LESLIE

P.S. My copy of the OED offers no entry for “Kiwi” in the sense of native New Zealander or scrumptious dessert, only for the Maori-derived name for the bird whose Latin name is apteryx, or “wingless.”