Julia Kriventsova Denne is a teacher of Russian literature and Russian language based in the Chicago area. She teaches several classes (at several Chicago-area sites and via the internet) for teenagers and adults, promoting an appreciation of Russian history, literature, and language. Denne studied linguistics and literature at St. Petersburg University in Russia. In 2005, she started the Life Readers: Classics Study Group at the Arlington Heights Memorial Library for people interested in serious, longer works, and she has been teaching seminars at the Newberry Library in Chicago since 2007. In addition, she has taught Russian Literature, history, and film for gifted homeschooled teens in the Chicago area. Last year, she launched her website, By the Onion Sea, in order to teach online literature classes for teens and adults. (For a full and fascinating explanation of the name, click here.) Besides literature, Denne offers instruction in the Russian language, and her students have won numerous prizes at the Olympiada of Spoken Russian and the Russian Essay Contest.

Until I met Julia, in 2007, the deep and thought-provoking world of Russian literature was closed to me. For this subject, I needed a teacher! Through her expert and generous guidance, I have become acquainted with many authors who have enriched my life. My daughter, too, now studies with Julia Denne, and is learning to think and write with increasing depth about the structures and intriguing ambiguities that make great literature so challenging and rewarding. I was very happy that our teacher agreed to respond to a few questions, and I hope you will enjoy this peek into the literature of another part of the world. Be sure to scroll to the bottom for a list of her top ten recommendations! (Note: The illustrations interspersed throughout the post were all selected by Denne and are in the public domain.)

You grew up in Petersburg, Russia. Would you describe your training in literature? How does it differ from what most of your students’ backgrounds?

I was studying English, literature and linguistics at the St. Petersburg University in the 1980s. It was the Soviet time called “the period of stagnation” when it was illegal for me to read Nabokov on the subway. I read it anyway, in English, so few people could understand what I was reading. At the University, I had a very formal and traditional approach to studying literature. Reading was emphasized: my summer reading list had more than 50 works, some of them quite substantial. We started with the Ancient Greeks and made our way through the Middle Ages, Renaissance, and Enlightenment to the mid-20th century. I wrote papers, but all my literature exams were oral. If I didn’t read something well, the professor was fast to discover it, almost immediately. Nothing could save me, and so I did my reading. I remember discovering Diderot and talking my friends into reading his novels. I find such chronological comprehensive reading to be a great advantage to my teaching now. Frequently, it is possible for me to see how the cultures and writers connect, and putting pieces together gives some clues that make our discussions thought-provoking.

Could you comment on the rewards and frustrations of introducing Russian literature to American students? Since you teach all ages, does this differ with the students’ age?

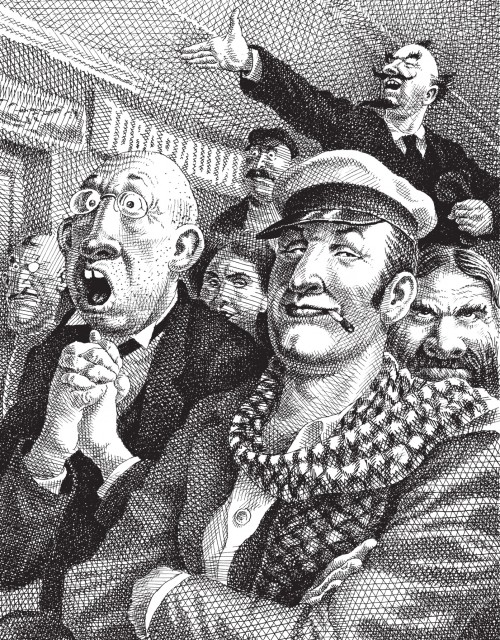

I am always amazed by how fast my students grasp the smallest cultural and historical details right after my explanations. Though most of them have never been to Russia, it doesn’t prevent them from loving and understanding the literature, and of course that is very rewarding for me as a teacher. I love teaching my Newberry adult seminars. The participants come from all backgrounds, and most of them are very well-read and have interesting life experiences. This is reflected in our discussions, and I always learn something new from my students. Teaching teens is very different. They are more used to reading straightforward, plot-driven fiction or fantasy and science fiction novels, so Russian weird, idea-driven “baggy monsters” (Henry James’s characterization of works like War and Peace) puzzle them at first. That is why I prefer to start with short Russian fiction, which is still weird and idea-driven, but at least it’s easier to get used to. Everyone finds something that works for them in Gogol’s stories – the fantastic, the exaggerated reality, the grotesque, or the trivial that becomes not just banal, but evil. In reading the longer novels, younger students gradually realize that the thoughts that Dostoevsky’s or Tolstoy’s characters are struggling with are universal. “What is bad? What is good? What should we love and what hate? What do we live for? And what am I? What is life, and what is death? What power governs it all?” asks Pierre Bezukhov in War and Peace in one of the not infrequent periods of his life when everything “within and around him seemed confused, senseless, and repellent” (War and Peace, Book 2, Part 2). These are the same thoughts that have always occupied most teenagers. I have seen how younger students get engrossed in the so strange, but also so familiar life of the19th century Russia.

Regarding challenges, well, I may be wrong, but it seems to me that many younger students prefer reading fantasy and science fiction, living in some other worlds that have their own laws and affairs. Even Jane Austin’s novels present to them a fantastic world with very isolated structure and characters so different from modern people that they become comfortably unreal. Younger students are not as happy when the fantastic, the satirical, and the realistic remind them too much of the world they live in now. They are not used to it, and sometimes they struggle to distance themselves from such worlds by harshly judging the writers and the characters. My aim is to convince them not to dismiss a difficult writer but to understand the writer’s intention. I try to bring as much background information as possible to explain the time and the place so that students could imagine what life was like in a specific community. It is difficult for the young to see the gray and to get into the complexities of human nature. They want to solve the disturbing and the frustrating, which is not always possible.

As a teacher of both language (Russian to native speakers of English) and literature, you have an unusual dual perspective. Could you comment the connections between literature and language?

When I start teaching Russian, I introduce Russian poetry right after learning the alphabet. We start with short children’s poems and progress to Pushkin fairly soon. Pushkin, Lermontov, Pasternak, and Akhmatova are primarily poets, and you can’t understand why Russians are so crazy about them from reading the translations. They used Western forms but filled them with Russian content, and translations frequently can’t do justice to verse. I actually have a student who decided to take Russian after she heard me read a poem in Russian during our literature discussion. Kids still memorize poetry in Russia, and my students do it as well. We discuss each poem in detail, and they learn to recite the poems beautifully. Many poems have been set to music. I have a student who has a beautiful voice, and she has recorded the songs she sings in Russian.

Would you comment on the link between reading and writing about what has been read?

Reading is more receptive, while discussing and writing about what one has read is more active. I structure my classes so that the students participate actively with what they have read. In addition to weekly class discussions, I ask students to write one paragraph of response each week. They can choose from a number of writing questions I provide as prompts. And I then share these reactions with the group. The immediacy of this helps the students distill something from their current reading, and it also helps me to realize which themes are understood less; interesting connections; a variety of opinions.

I also assign two longer formal essays for each semester class. As with the weekly paragraphs, students can choose from a long list of possible topics or propose their own. For each essay, I work with each student independently, providing extensive comments over several drafts. This allows the students to understand the necessity of revisions, and yields fewer–but better-written–essays.

You teach students in person, one-on-one, in small groups, and in larger groups, both in person and online. Could you comment on the pros and cons of online versus in person instruction?

I prefer teaching Russian one-on-one or creating a very small group. When I tried teaching Russian to a larger class, I discovered that everyone learns languages differently. Some have better memories, others work harder. Some prefer learning grammar through tables, others need a lot of conversational practice to make grammar work. The individual approach becomes a necessity. For teaching Russian literature, I prefer larger groups which include adults and teens of different backgrounds and experiences. I emphasize discussion, and discussions work best not in a homogeneous group, but in a setting where a variety of opinions is introduced and commented upon.

Are you planning any new courses?

Yes! Online, I will be teaching Tolstoy’s War and Peace in winter/spring 2014 (registration is currently open), and I am preparing a couple of workshops for summer 2014: Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground, which is a very challenging and disturbing novel that is essential for understanding Dostoevsky; Gogol’s The Government Inspector, which is the funniest comedy in the Russian language; and Turgenev’s First Love and Spring Torrents, which have powerful female characters and are beautifully written. In the fall of 2014, I will add a new course “Russian and Soviet History from 1900 to 1940 through Literature, Art, and Film.” We will read John Reed, Maxim Gorky, Zamyatin, Olesha, and Bulgakov and discuss Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Dovzhenko, and Vertov’s movies to examine life in the Russian Empire, the Russian revolution, and Stalin’s terror.

At the Newberry Library in Chicago, I will be teaching Tom Stoppard’s The Coast of Utopia in spring 2014 and Dostoevsky’s Petersburg Short Fiction in summer 2014.

Who are your all-time favorite writers?

This is an impossible question! I can’t really choose, so I offer a list of ten wonderful texts (below), in English translations that give a sense of the work in the original. For me Russian literature encompasses all the writers and poets, and singling out one or another seems wrong to me. I do love them all, though I may sometimes reach for Gogol, while Turgenev appeals to me more on a different occasion. I would choose Tolstoy’s War and Peace as a quintessential encyclopedia of Russianness, and it could be a good introduction to Russian literature if you have some guidance. In Russian schools, students read War and Peace at age 14 or 15 (it could be a little later nowadays), and when you’ve read War and Peace, you consider yourself an adult. You live with Natasha Rostova, Pierre Bezukhov, Marya Bolkonskaya, and Andrei Bolkonsky for a long time, and they stop being just characters in a book. They become your friends, and you learn how to live with them. None of them is “positive,” and they make lots of mistakes. Still, you care for them and grow up with them and through their struggles and quests.

Julia’s recommendations (Texts and translations, in no particular order)

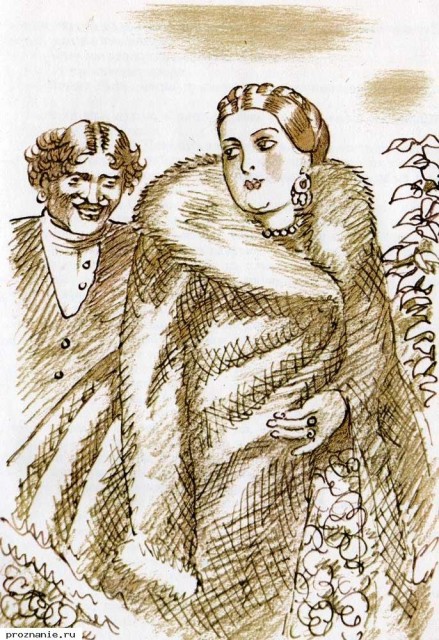

1. Ivan Turgenev’s First Love (Constance Garnett translation), a novel that is on the borderline between prose and poetry. It is a study of a tormenting passion and a devastating loss of innocence.

2 and 3. Nikolai Leskov’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk (Robert Chandler translation), which is as intense as Shakespeare, and Nikolai Leskov’s The Enchanted Wanderer (Ian Dreiblatt’s new translation is a must), a picaresque folk adventure novel.

3. Nikolai Gogol’s The Government Inspector (Ronald Wilks translation), a biting and hilarious play.

4. Mikhail Bulgakov’s Heart of a Dog (Mirra Ginsburg translation), which I consider the most ferocious anti-Soviet satire ever written.

5. Mikhail Lermontov’s A Hero of Our Time (Paul Foote translation is good) is considered the first novel of psychological realism in Russian.

6. Yuri Olesha’s Envy (translated by Marian Schwartz). We are plunged in the extraordinary narrative from the famous first sentence, “In the mornings he sings in the toilet.”

7. Russian Magic Tales from Pushkin to Platonov (translated by Robert Chandler). Half of the tales here are true oral tales, while others are re-workings by four Russian writers, including Pushkin. Russian tales are weird!

8. Ivan Goncharov’s Oblomov (translated by Stephen Pearl) is one the most popular, winsome, and delightful Russian novels. It has become standard reading in Russian schools. If you mention it to a Russian, the response will likely include “Oblomovism” (“oblomovshchina” in Russian), a term from the novel that entered the language to indicate sluggishness, apathy, and inertness. It has also become a catchword for the condition of the Russian gentry, Russian backwardness, and even the Russian soul. Oblomov, the main character, who prefers daydreaming to doing anything, could be judged as an aristocratic parasite or looked at as a holy fool, but his laziness and good-natured idleness have a seductive appeal.

9. and 10. The Twelve Chairs by Ilya Ilf and Evgeny Petrov, and its sequel, The Little Golden Calf, have enjoyed an immense popularity in Russia. Ostap Bender, the “grand strategist, or operator” is a con man on the make in the Soviet Union during the New Economic Policy (NEP) period. He is obsessed with getting one last big score—a few hundred thousand will do—and heading for Rio de Janeiro, where there are “a million and a half people, all of them wearing white pants, without exception.” Both Bender novels have been called “encyclopedias of Soviet life” and are indeed perfect catalogues of their time.

My thanks to Julia Denne for our conversation! Note: For more information on classes, click here.

Thank you for reading this! If you think of someone else who might enjoy it, please forward it to them. And, if you are not already a subscriber, I invite you to subscribe to the Wednesday posts I am sending out each week–it’s easy, free, and I won’t share your address!

Thank you for reading this! If you think of someone else who might enjoy it, please forward it to them. And, if you are not already a subscriber, I invite you to subscribe to the Wednesday posts I am sending out each week–it’s easy, free, and I won’t share your address!

Hi Dmitry,

So glad you liked it. Do you have a favorite work of Russian literature? Leslie

Thank you for your topic! Good illustration.